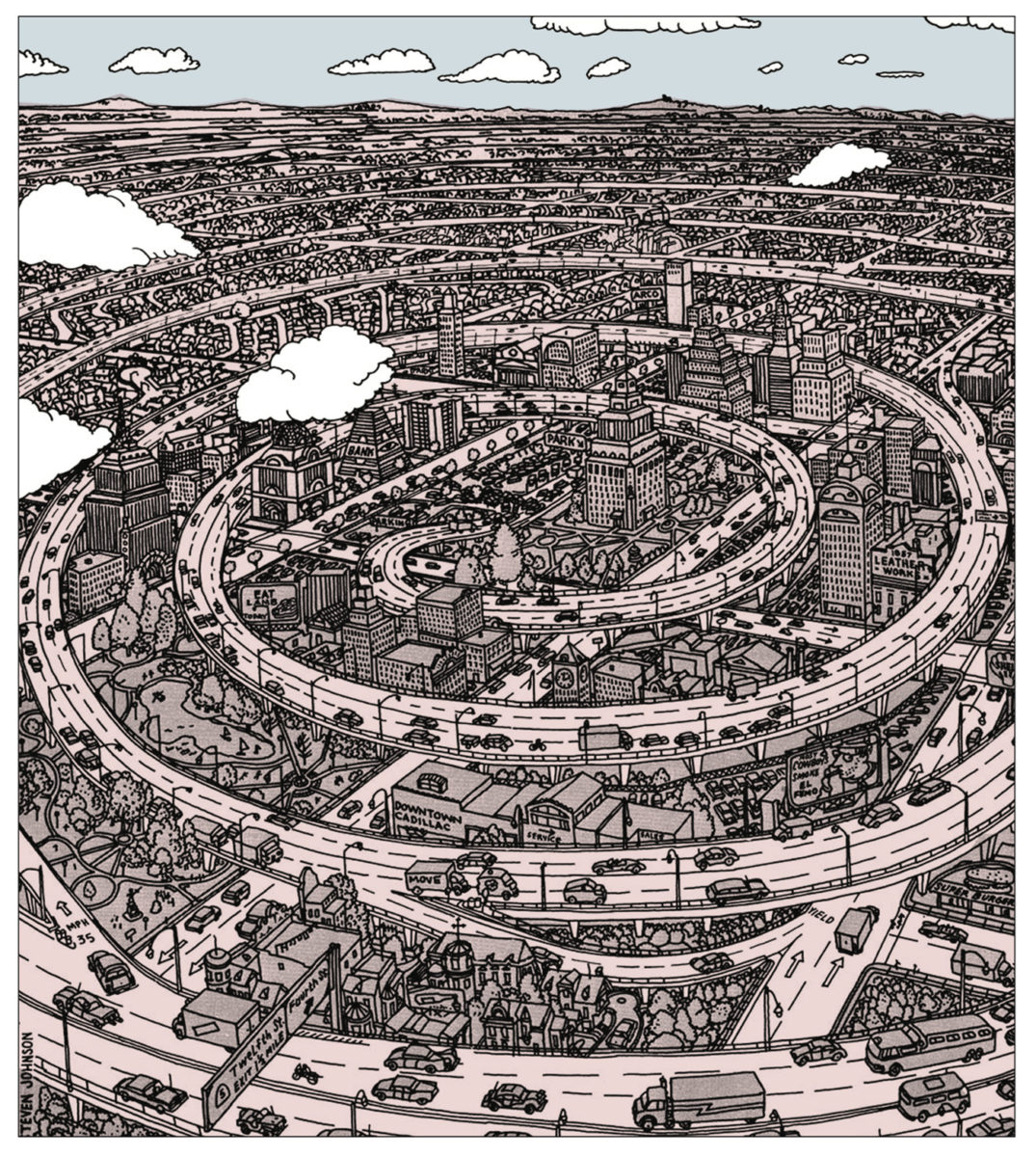

Thinking of nothing else, I would go inside the vault of my imagination and churn variations and combinations, morphing and combining ideas, giving birth to offspring.

Steven M. Johnson

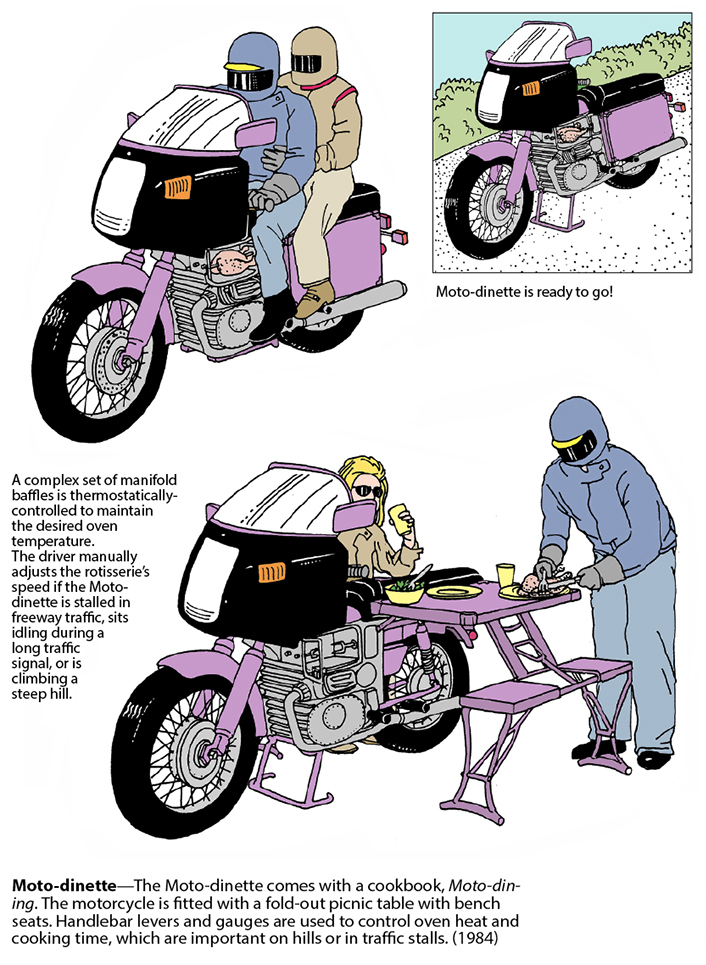

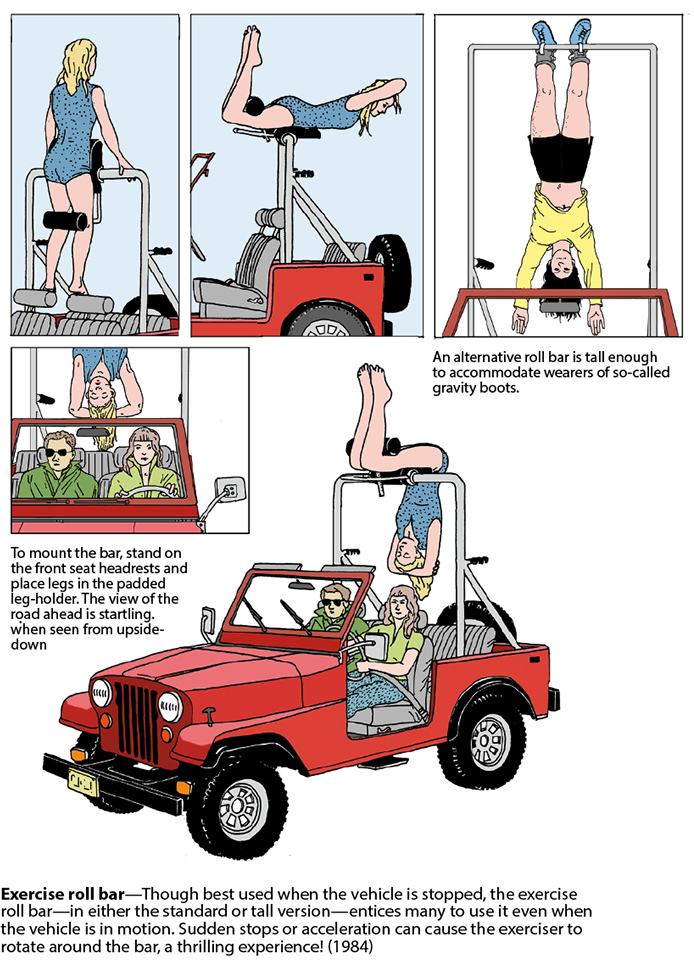

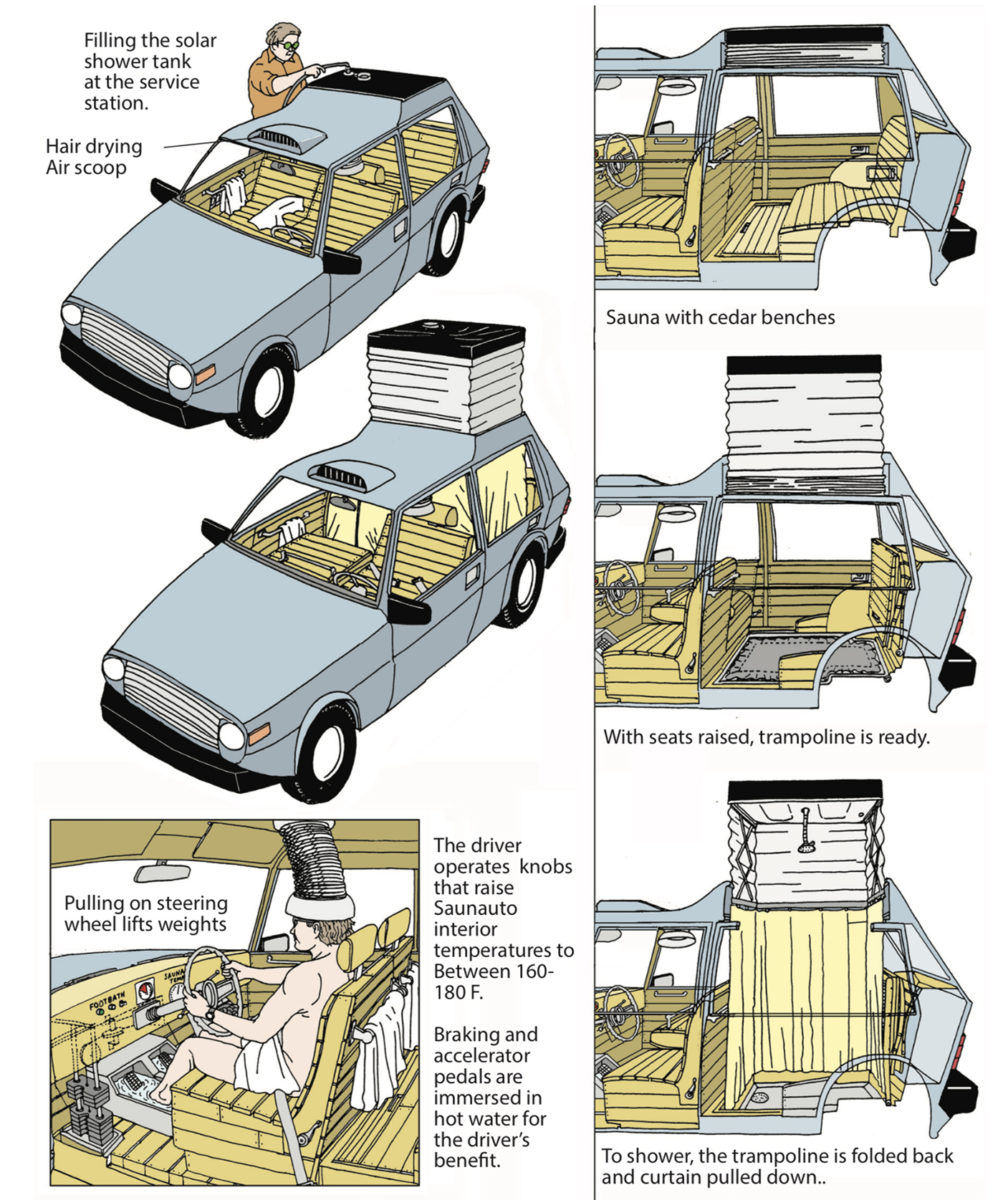

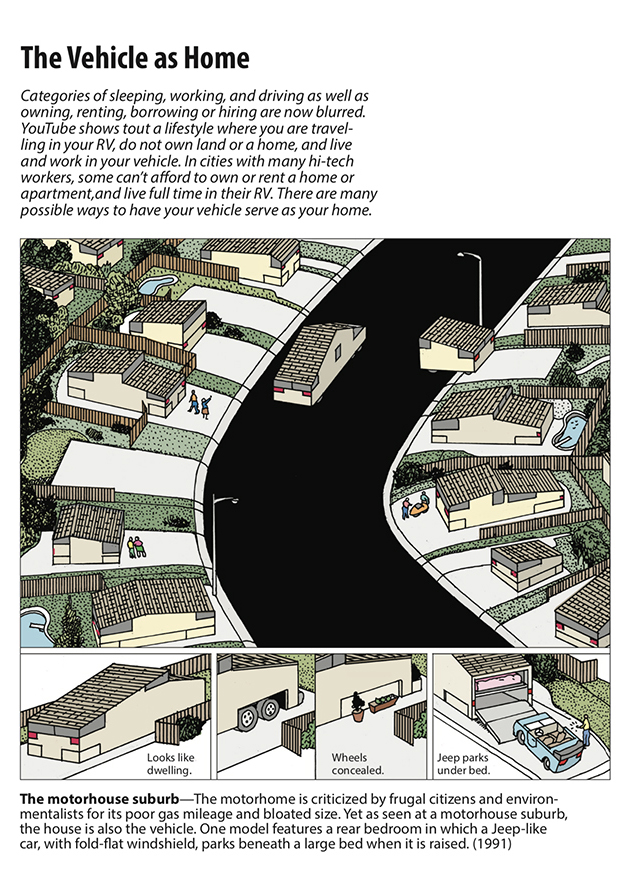

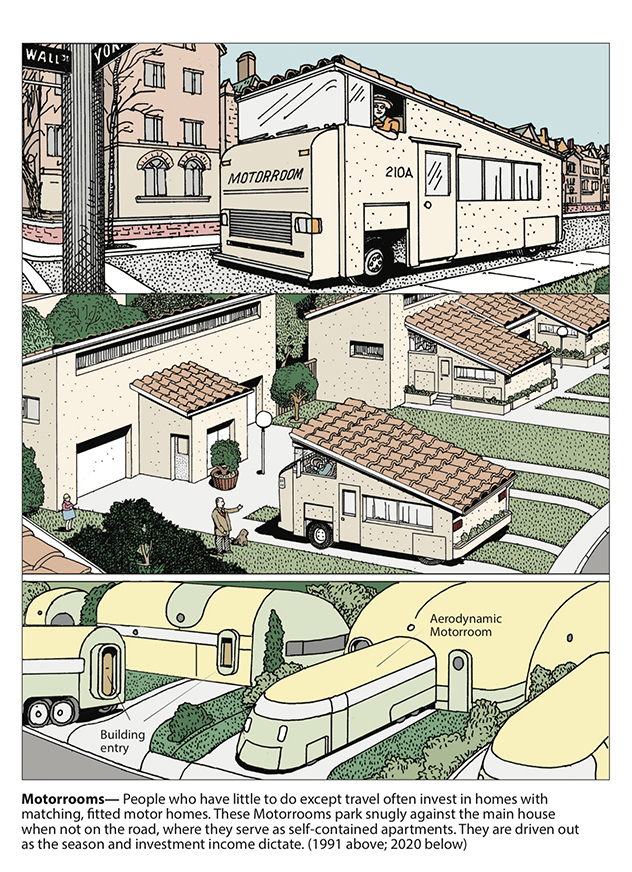

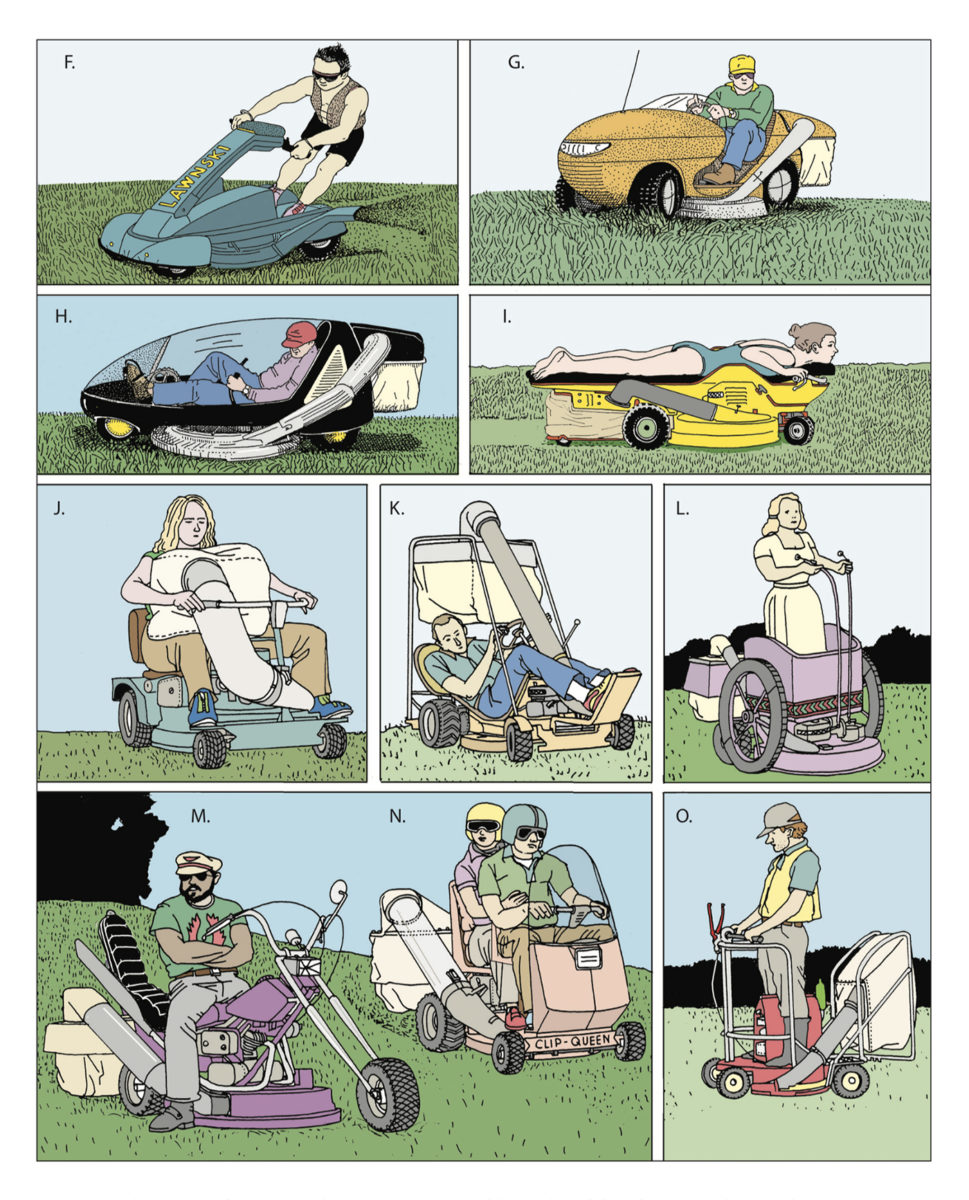

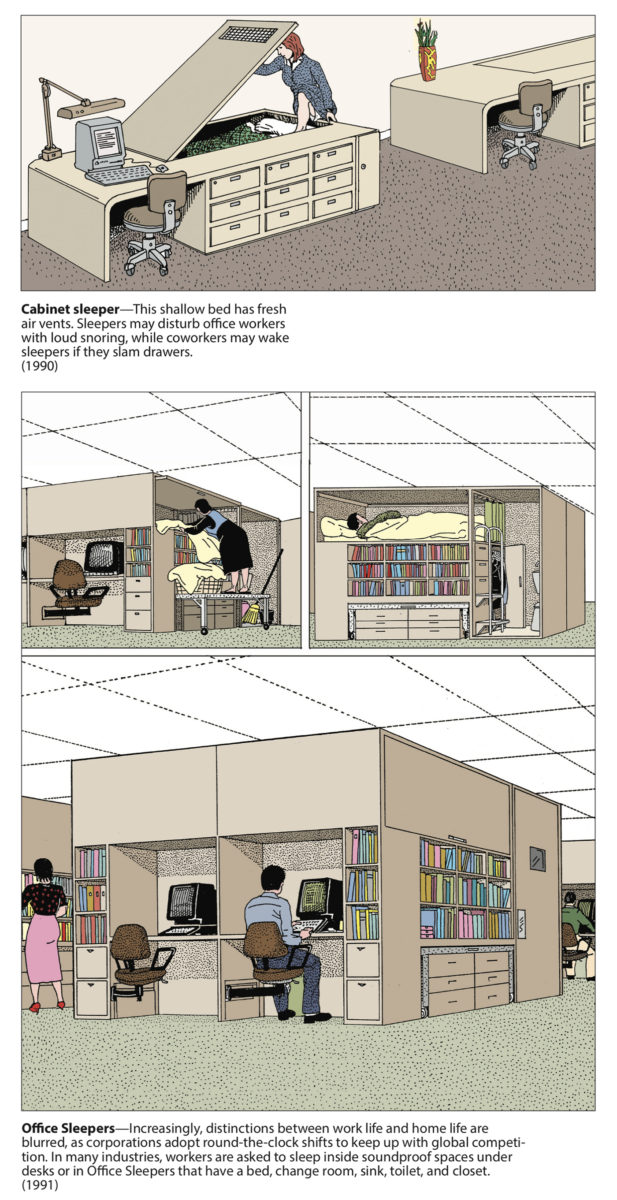

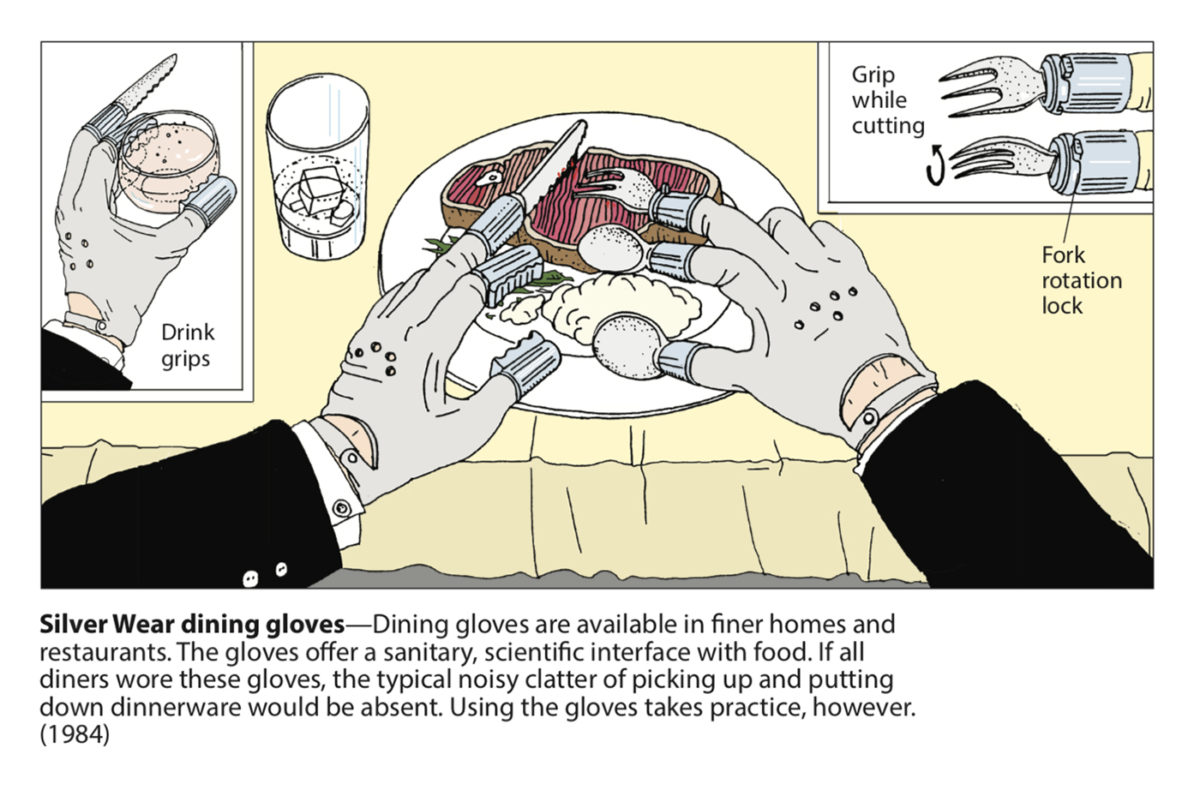

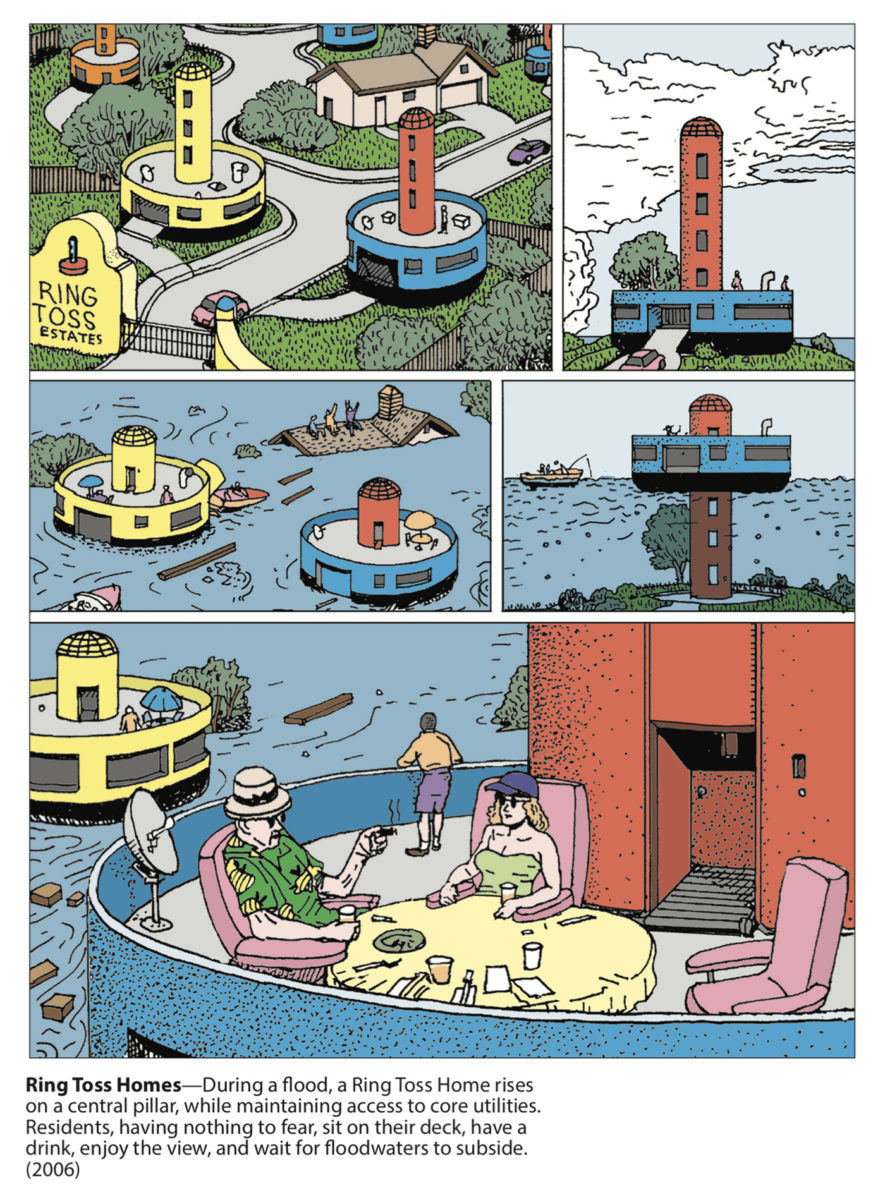

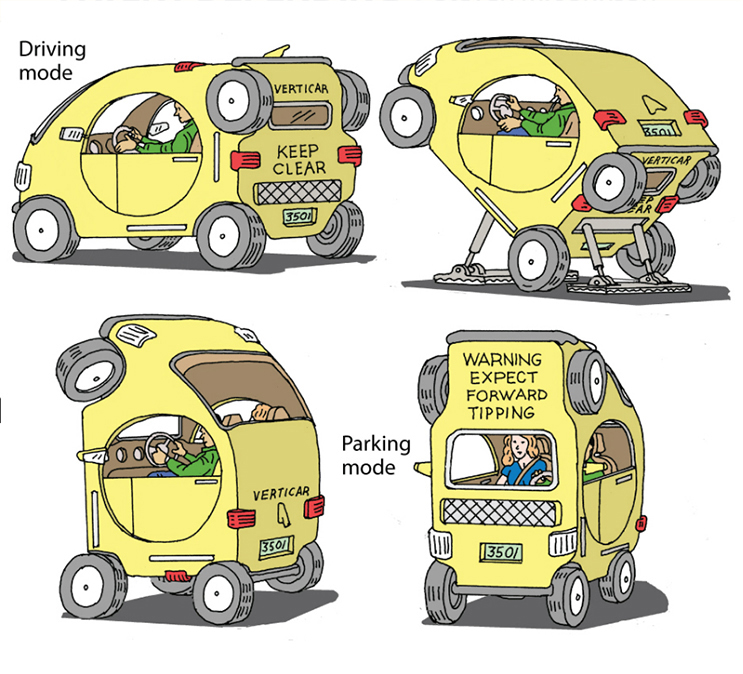

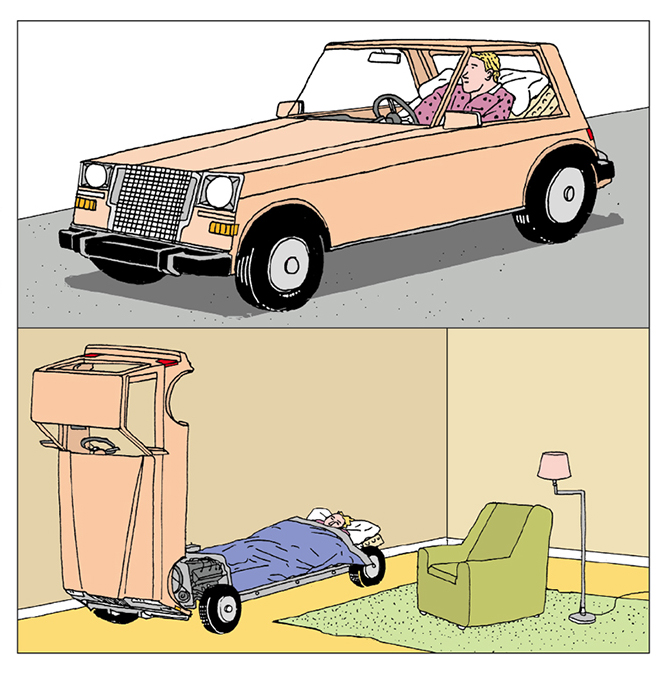

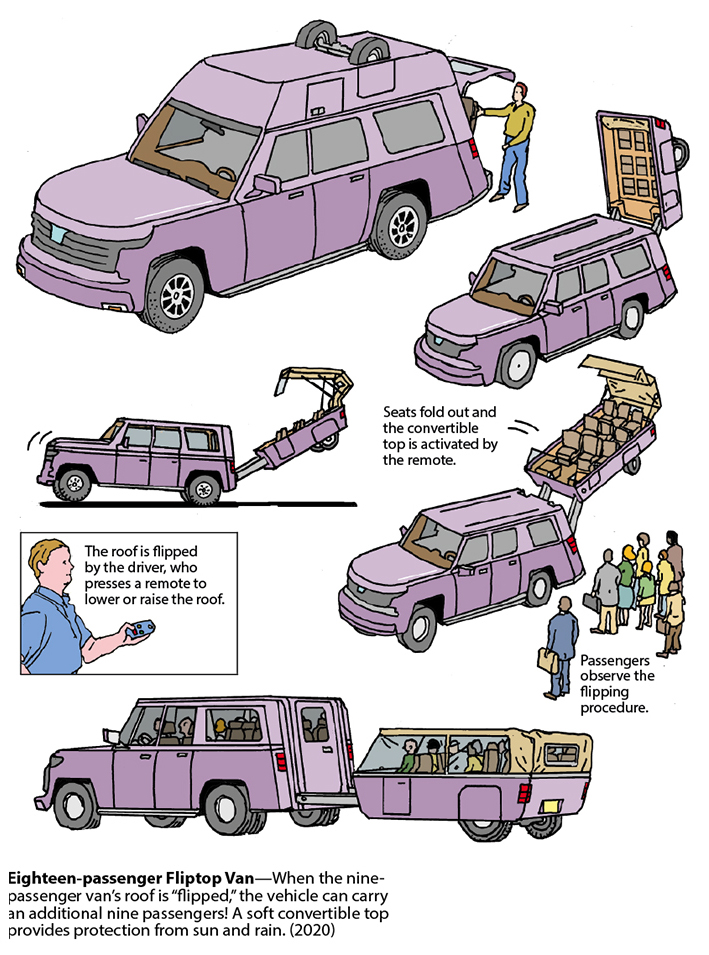

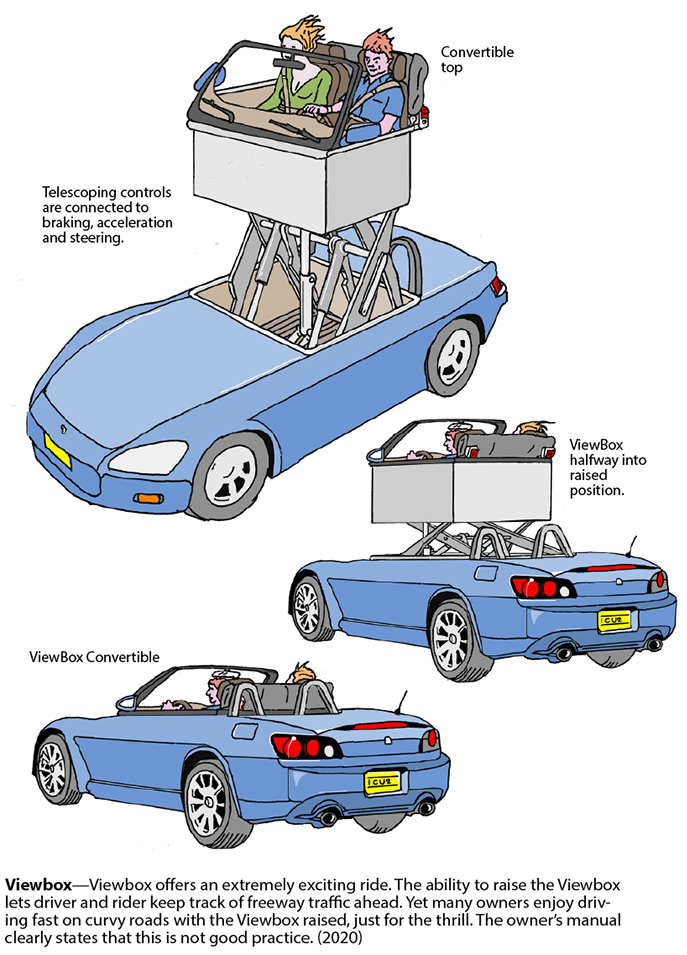

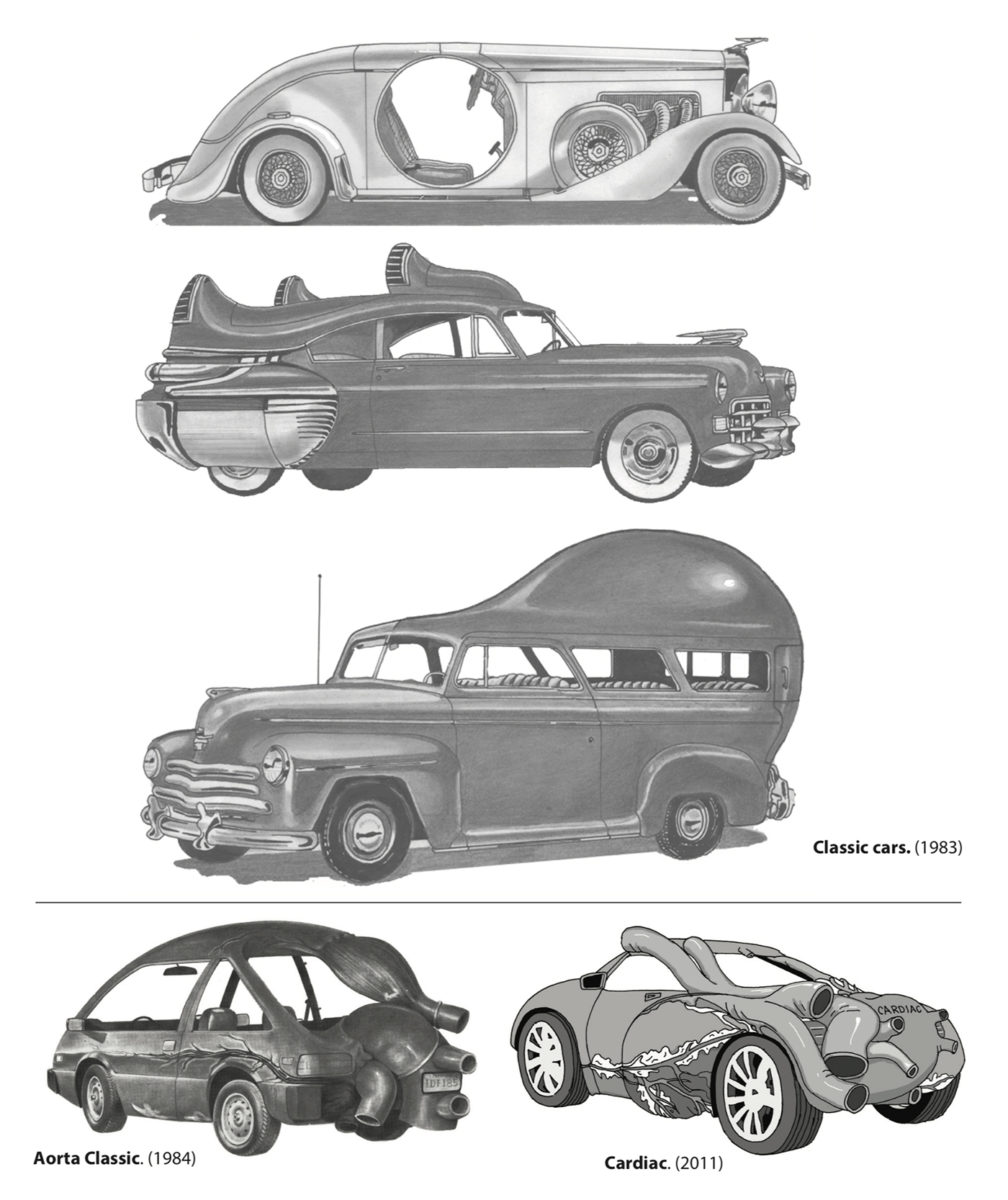

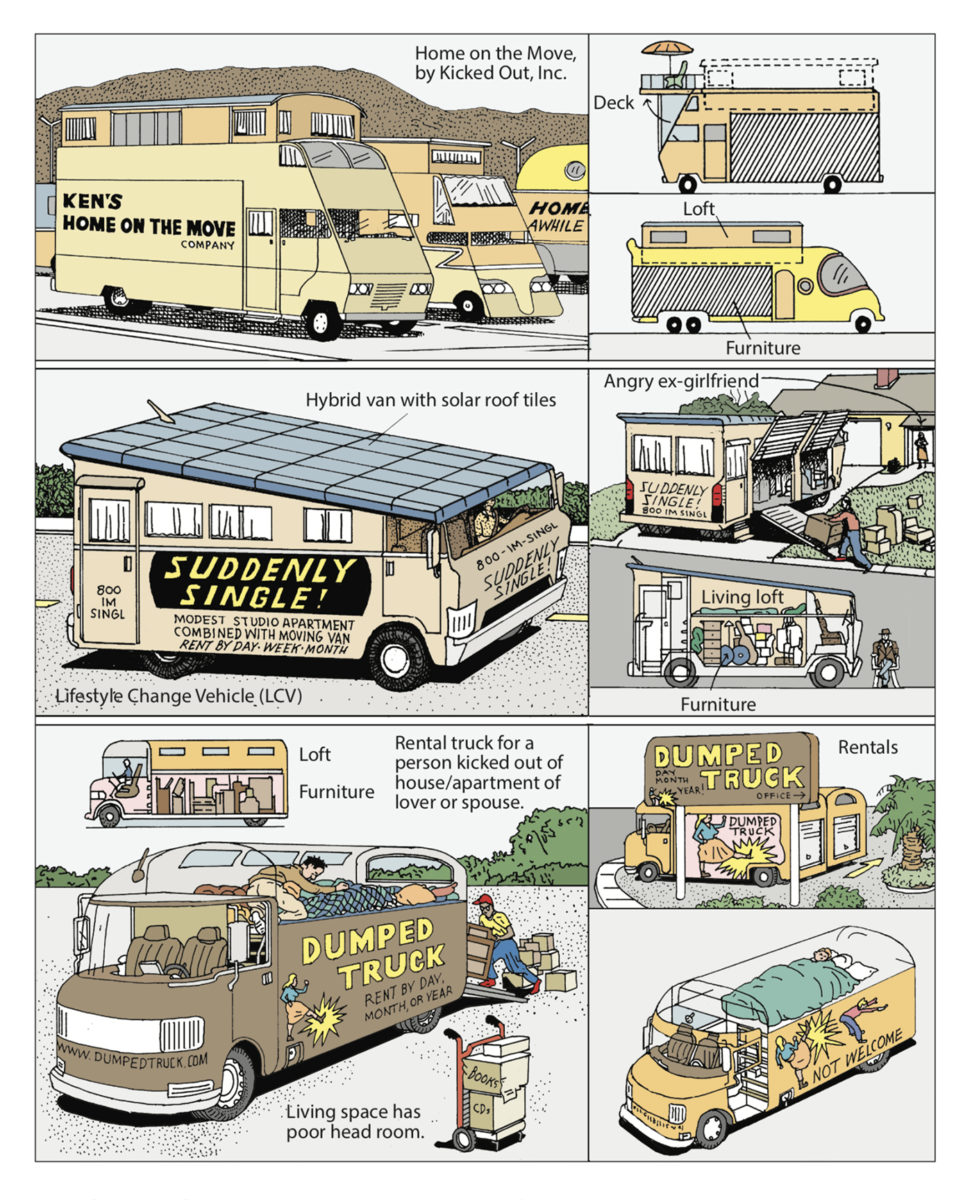

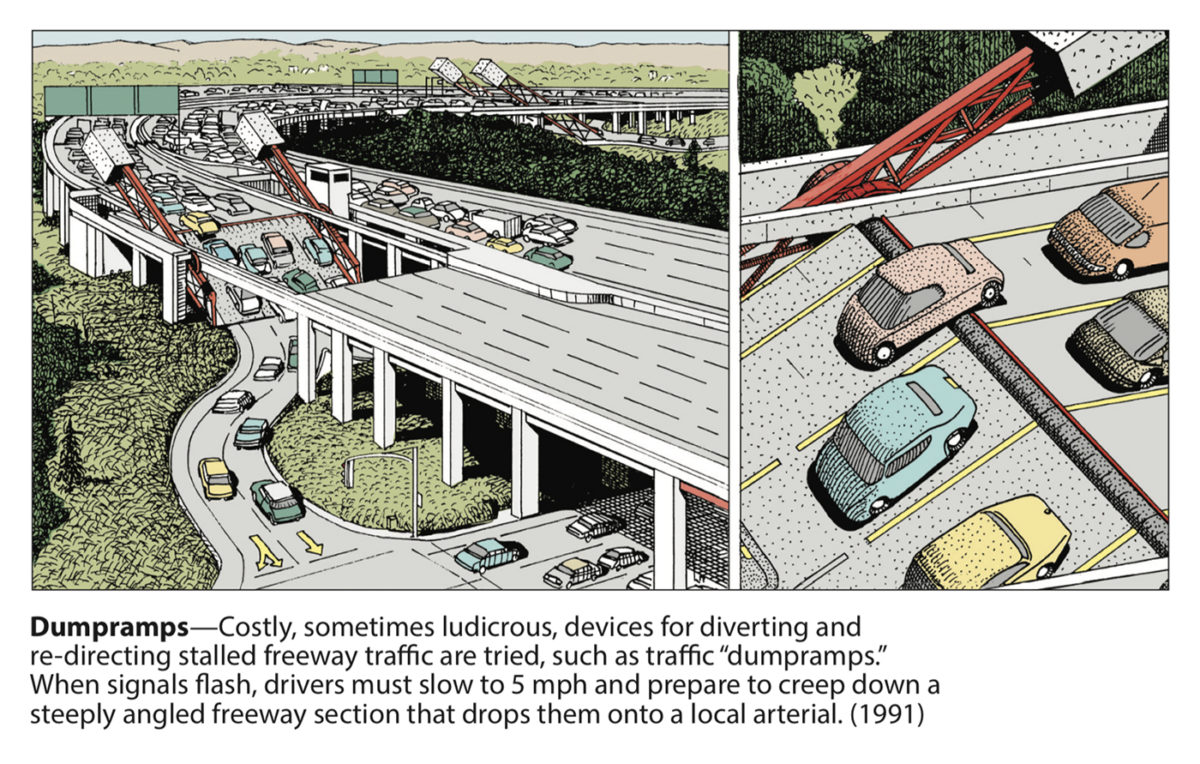

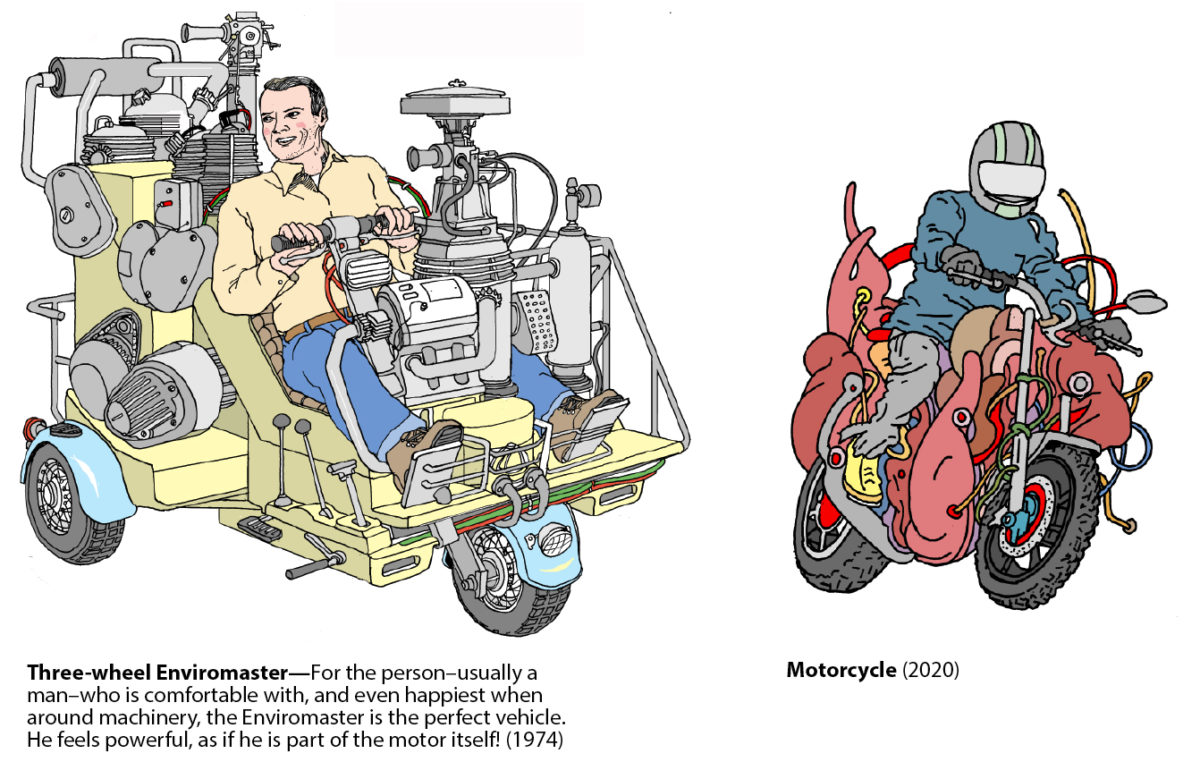

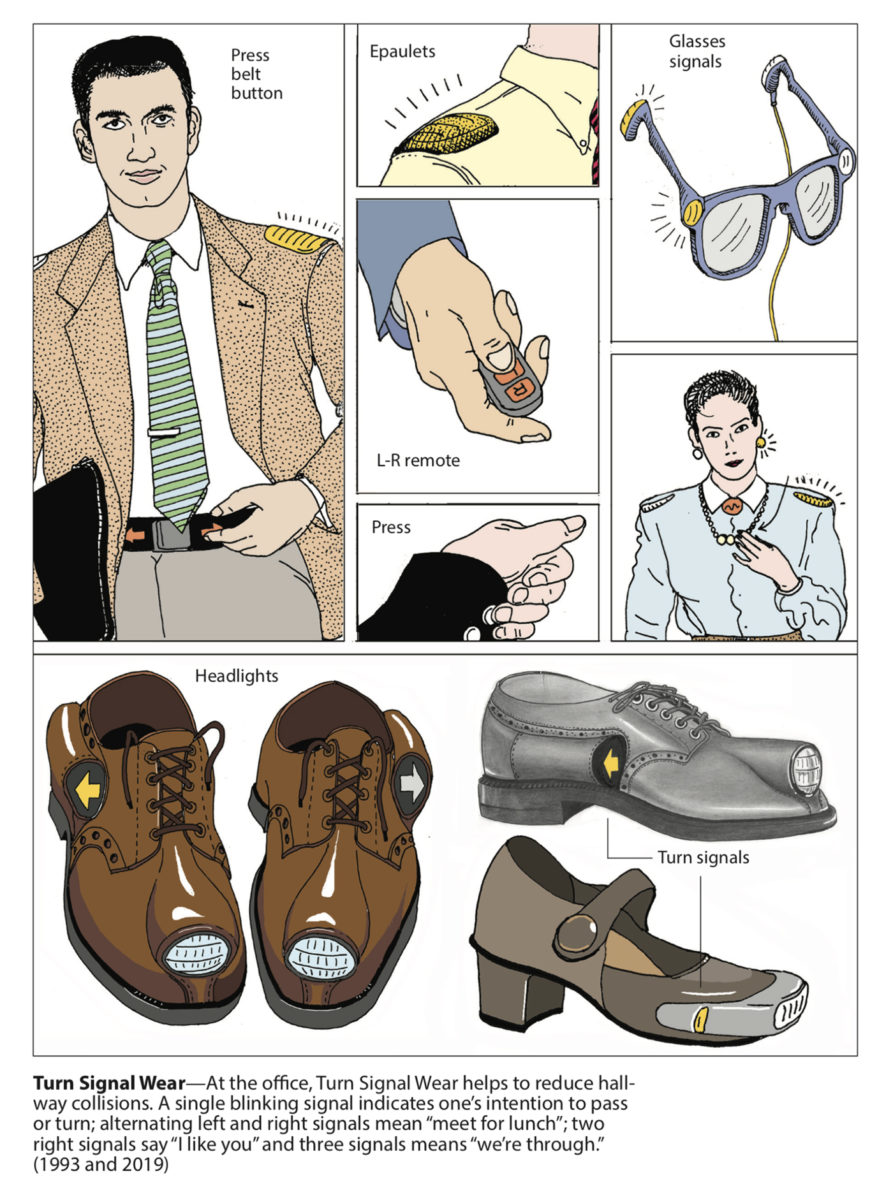

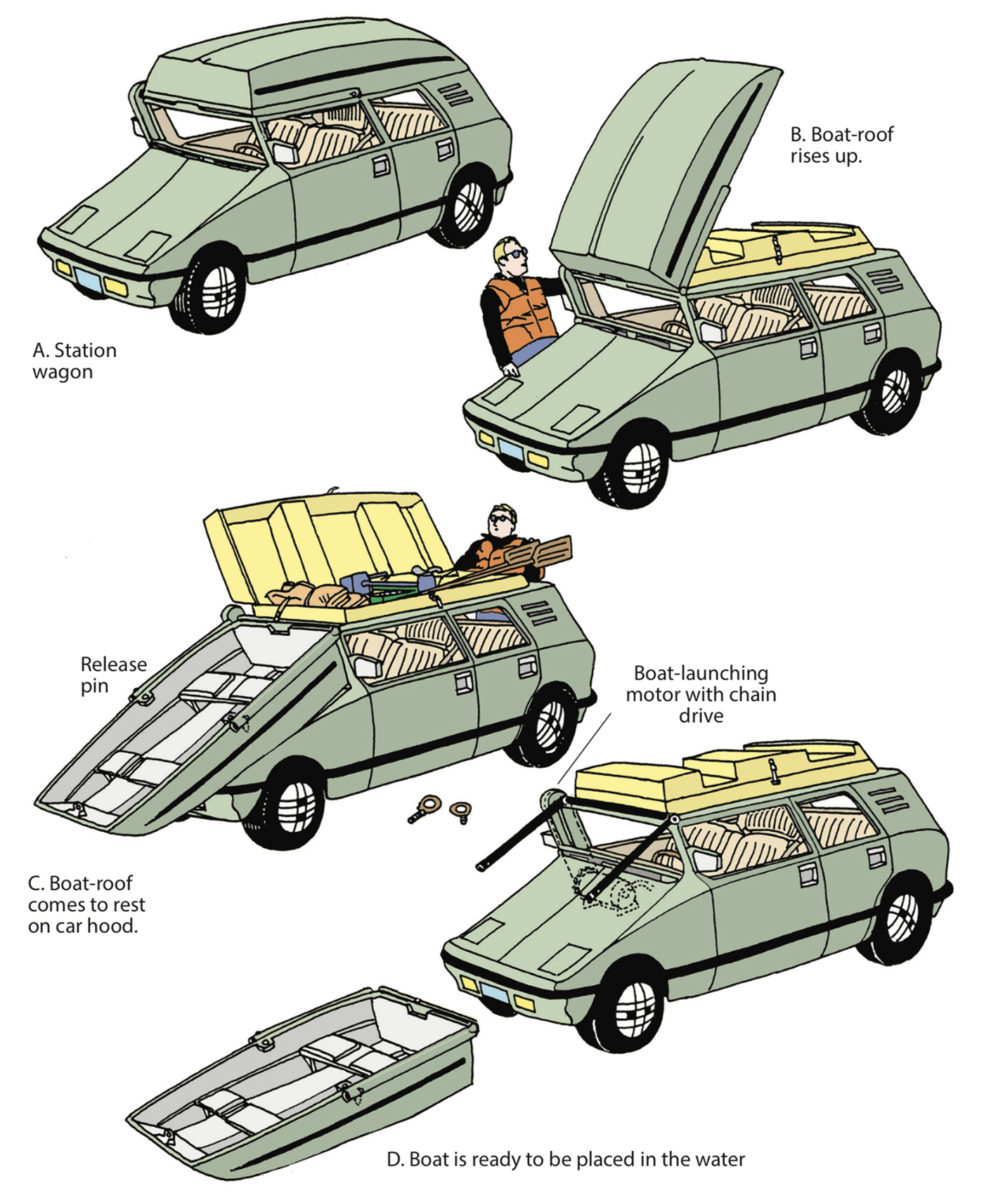

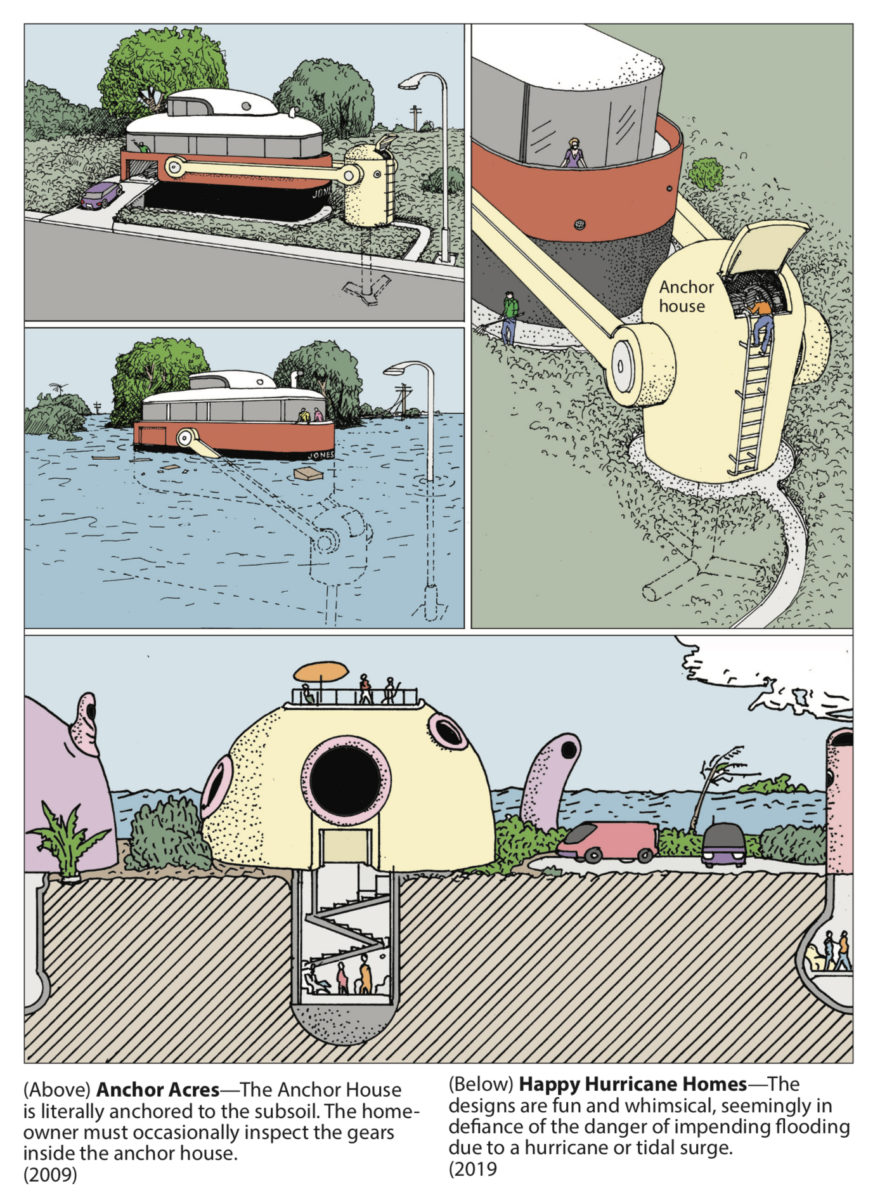

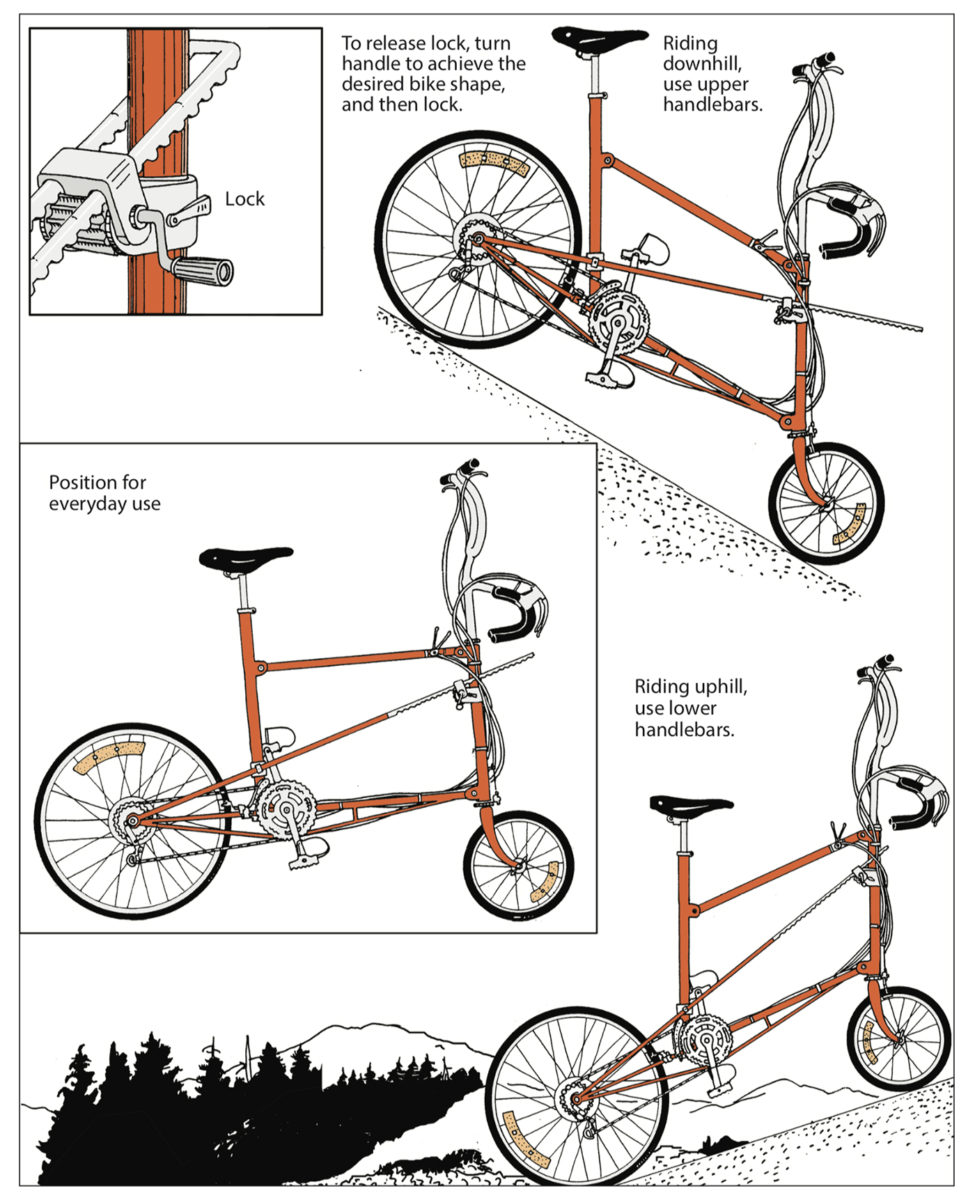

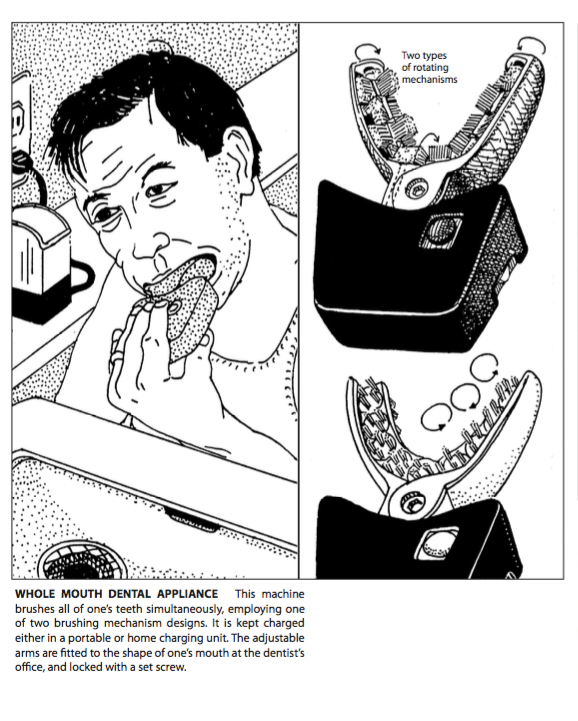

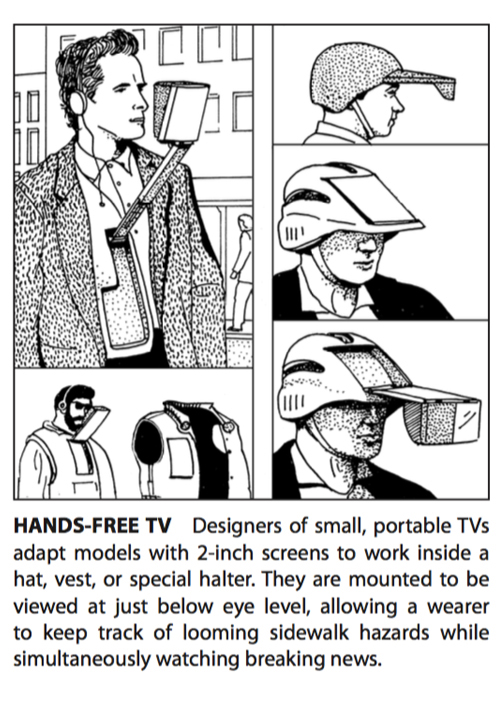

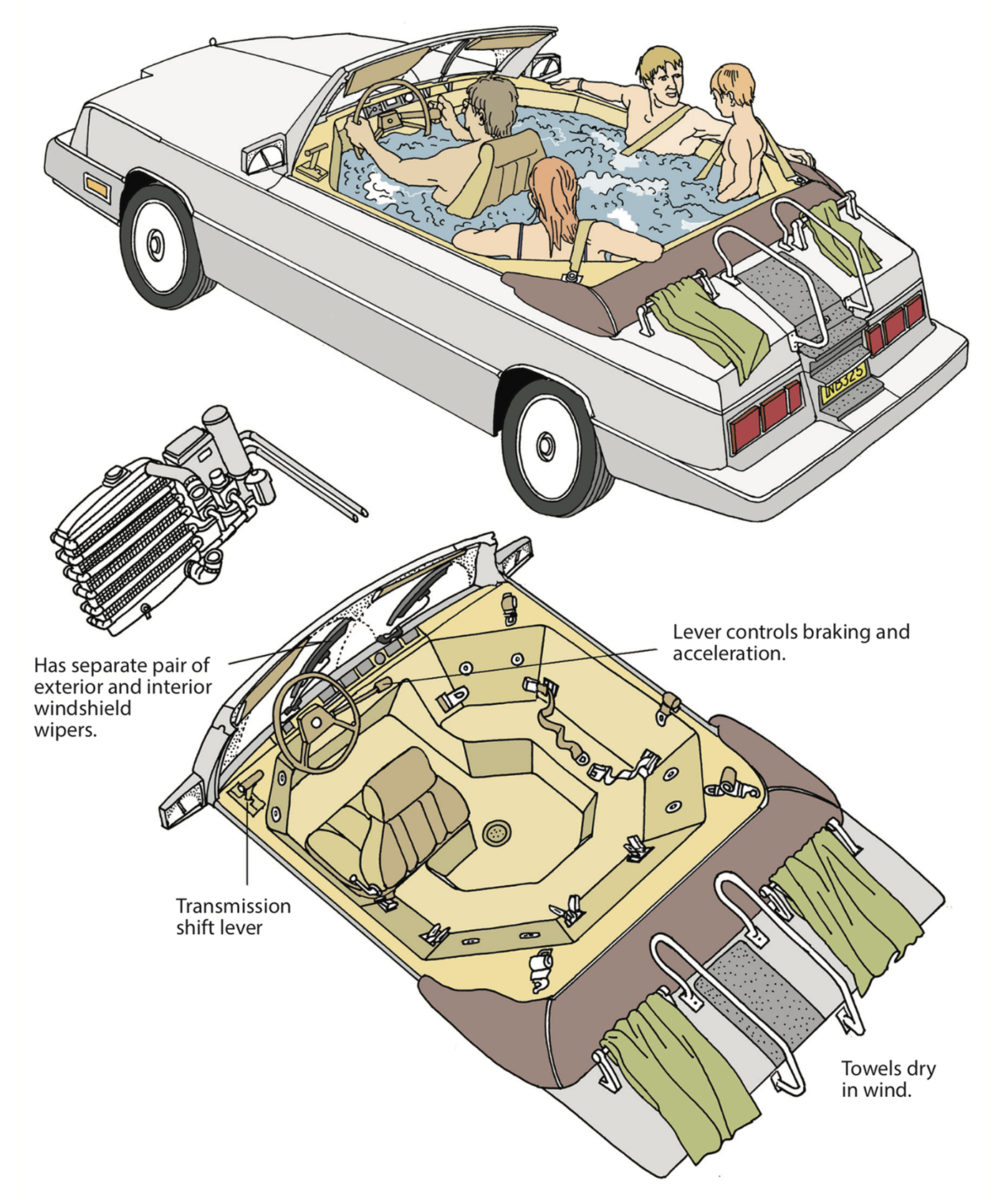

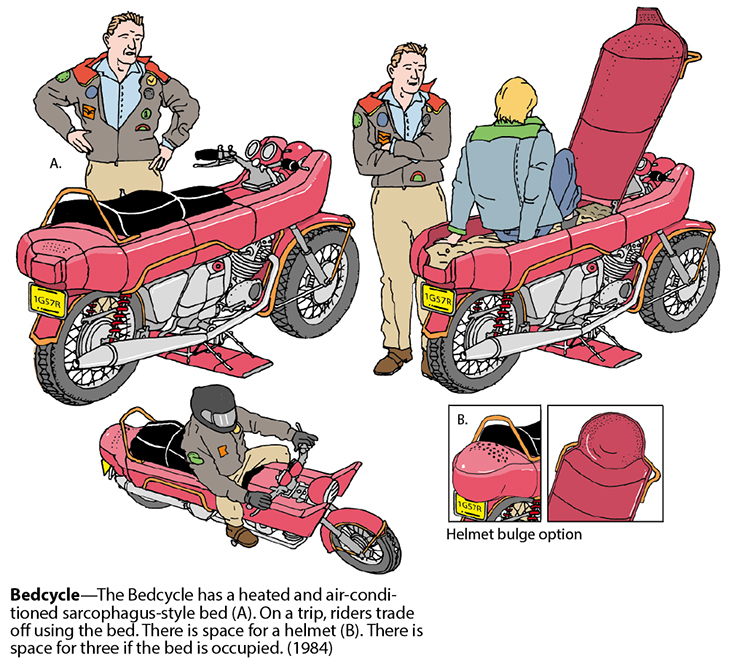

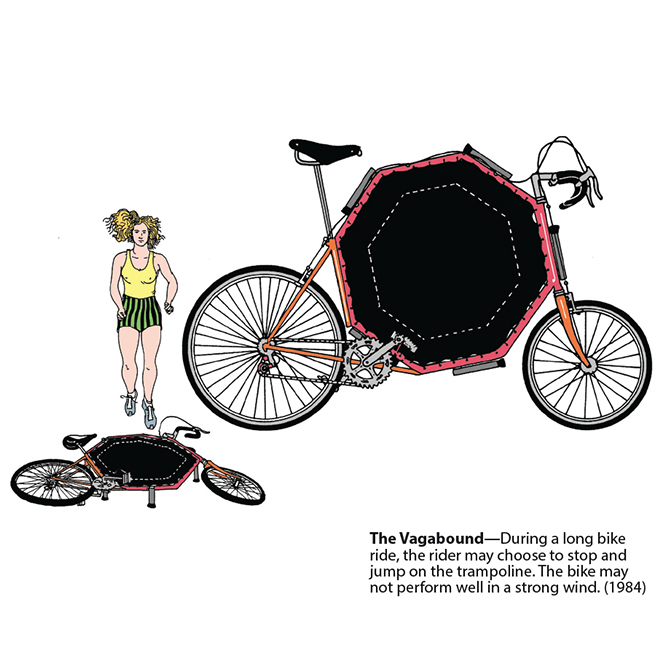

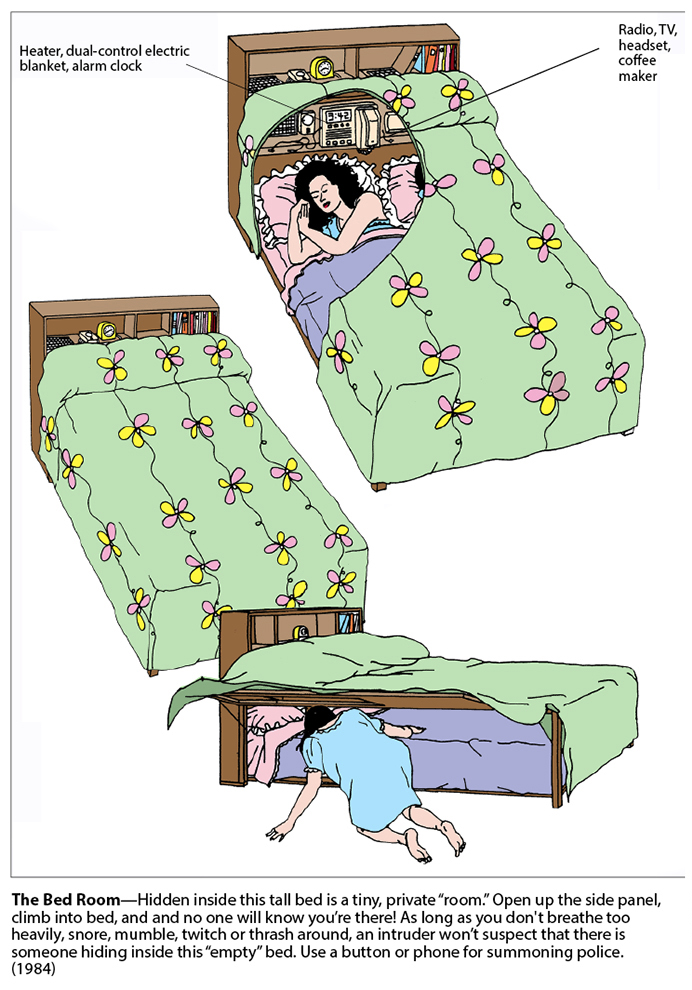

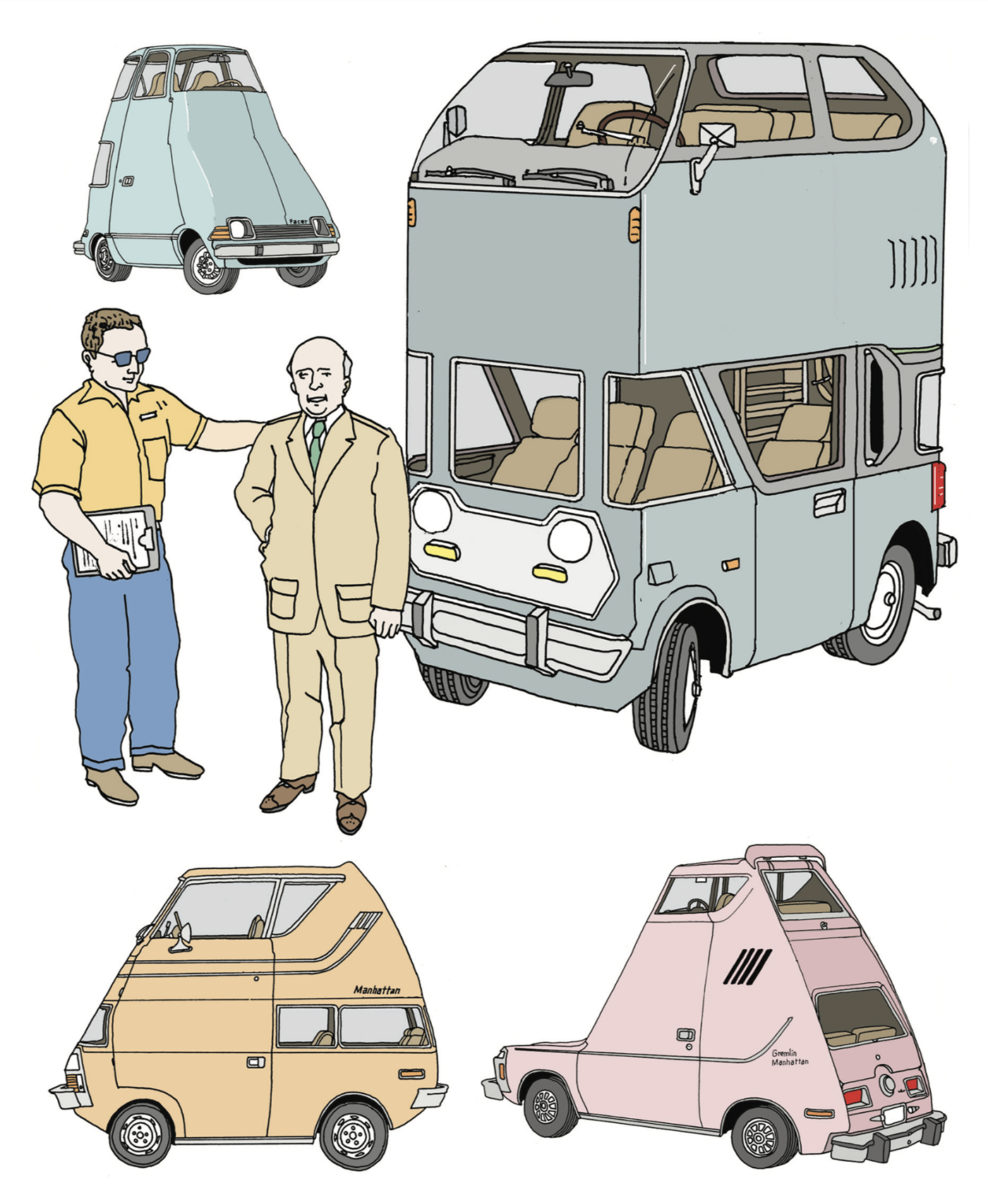

ART . November 5th, 2020Steven M. Johnson is an american illustrator born in the late 30s. Since the 70s, he created what may be the biggest collection of imaginary concepts ever made. Mostly vehicles but also cities, houses, furnitures, clothes,… everything really. We’ll share the tip of the iceberg here, check Steven’s books if you want to discover more.

____________

Who are you Steven?

I am 82 years old and live with my wife of 54 years in a suburb of Sacramento, California. I retired in 2004 from Honda R&D after careers as a city planner, newspaper artist and “futurist”. A portion of my free time now is involved with assembling, coloring and publishing my earlier invention-cartoons as well as in creating new work.

What can we find in your head?

What I choose to think about has changed over the years. In early school years, I thought about popularity and was class president sometimes. In high school, I thought about girlfriends, track and cross country running, and automobiles. (In the 1950s, pre-WWII vehicles in perfect running condition could be purchased for around $100. The last year of high school, I owned a 1929 Model A Ford roadster, as well as four other cars which filled my parent’s driveway in Palo Alto, CA.)

From age 25 to 28, I was a city planner by day, and at night an artist living inside an empty, unheated grocery store in Oakland, CA. From age 29 to 36 I studied meditation, astrology and esoteric New Age subjects in my free time. After I turned 35, I did cartoons for an environmental magazine, SIERRA, and suddenly discovered an interest in the process of inventing humorous, peculiar products. At 40, I became a staff artist at a newspaper and at 59 a futurist at a car company. This year, my head is filled with questions about what to do next.

How would you introduce your work?

My cartoon-invention drawings have always been created in black ink on white paper—any handy paper, including printer paper, wrapping paper I do not care. (A NYC gallery changed its mind about having a show of my work after seeing my work with White-out, yellowing Scotch tape, pasted scraps and drawings on paper that were not square).

The primary period of producing this work was from 1973-95 and then from 2009 to the present, after I was “discovered” by a New York Times columnist. Beginning in the late 1960s I had begun practicing meditation, and discovered how it produced an upwelling of energy and ideas that would energize my imagination. A side result was that it offered me an outlet for creating amusing, unusual products and a tiny income stream, selling my work to magazines.

When did you start drawing?

During school years, from third grade through Yale University, I was a competent natural artist, enjoying popularity because of it. It was a way of getting attention (and still is). In 1957, I took two semesters of pencil drawing taught at Yale by Bauhaus founder Josef Albers. We drew ellipses, circles, squares and parallel lines in pencil on newsprint pads until we grew sick doing it.

At that time, I learned how to discipline hand-eye coordination and the importance spatial thinking, allowing me to draw clearly and carefully. My spare, unadorned art style was somewhat along the lines of the work of the great Albrecht Durer, whose work I admired. I travelled around Western Europe alone on a motorcycle in Spring, 1961, making notes and drawings in a diary. On the trip, I developed a habit of using a Rapidograph pen. From 1963-65 in Oakland, CA, I secured stacks of large sheets of white or off-white paper free from a warehouse and drew directly with from subconscious thought without pre-sketching, always beginning in the lower left corner.

Do you know how many concepts you have come up with in total?

It would be difficult to calculate the number. Two books that are to be published in 2021 with Chinese captions by United Sky in Beijing include approximately 1,300 drawings, all in color. Those drawings are the “tip of the iceberg” as regards the number of ink drawings I have produced. For 22 years, from 1973-95, I drew unusual products and scenes from my imagination during weekends and nights after work. I have created similar work, less frequently or furiously, since 2009 up to the present time.

How did you find all these crazy ideas?

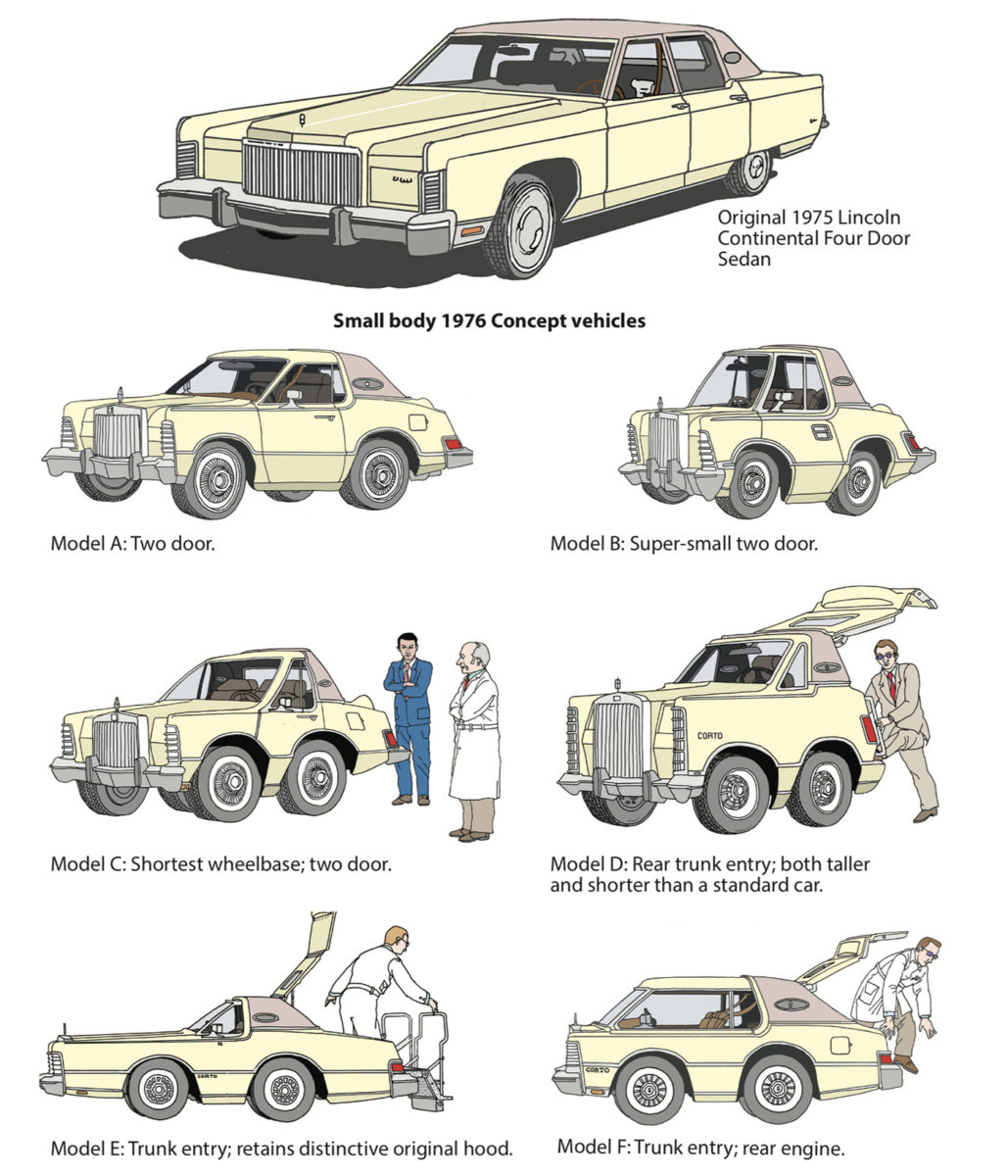

In March, 1974 an editor at SIERRA magazine assigned me to think up and illustrate 16 nature-destroying vehicles of the future. That weekend, I discovered an ability and a desire to come up with multiple solutions to a design problem. I produced 109 images, while falling into a mental process akin to falling half asleep; I would enter a so-called hypnagogic state. Thinking of nothing else, I would go inside the vault of my imagination and churn variations and combinations, morphing and combining ideas, giving birth to offspring. I would mix and match images. I created a kind of disturbed thinking in myself. This odd state of mind has never been my everyday state of mind, as it involves a very specific, intentional speeding up of images and ideas as if they are rolling around, clashing and colliding. I can enter this state even while driving a car on the freeway alone, but never in the context of conversing or interacting with a person.

Your inventions remind me of the work of the great British illustrator, William Heath Robinson. Is he a reference for you?

With my newfound ability after 1974, I saw that I had a fear of giving myself permission to imitate other artists or inventors, lest I lose my distinct focus and style, or begin to copy the work of others. I knew I was not a “real” inventor or product designer, so I chose consciously to not look up or study actual products.

In short, I preferred to spend time spinning out 20 ideas vs. focusing on a single idea. No, I was not aware of William Heath Robinson but was aware of Bruce McCall, born in Canada in 1935, whose “retrofuturism” concepts continue to grace the covers of THE NEW YORKER magazine. My work and Bruce’s work both employ exaggeration, unusual context and other tricks designed to create jarringly memorable and amusing images.

Did you or someone ever recreate one of your concepts in real life?

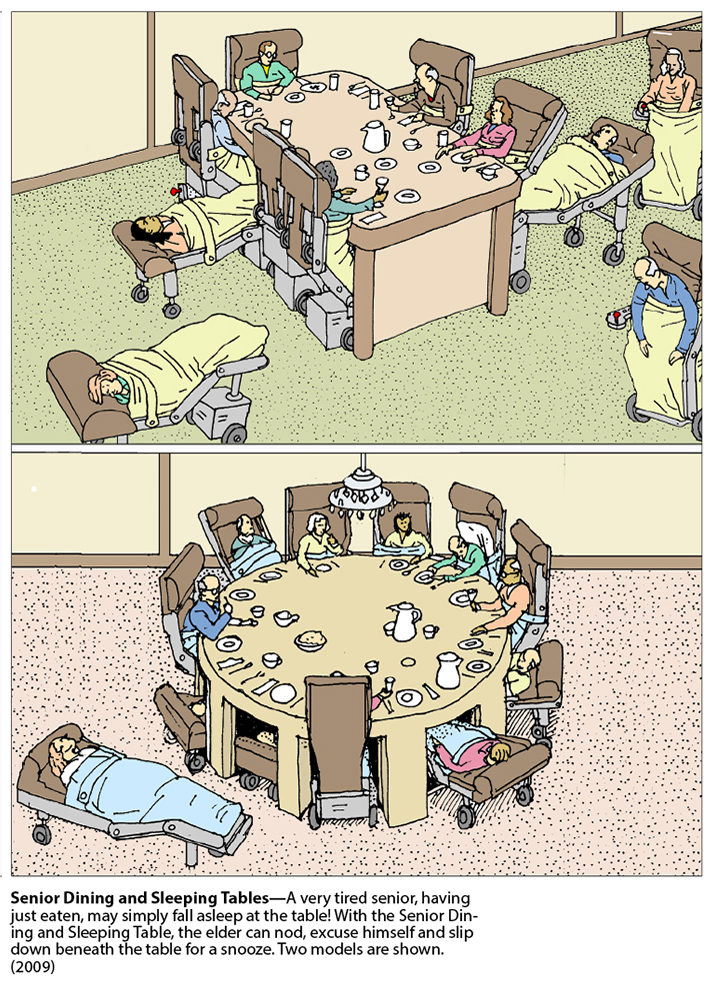

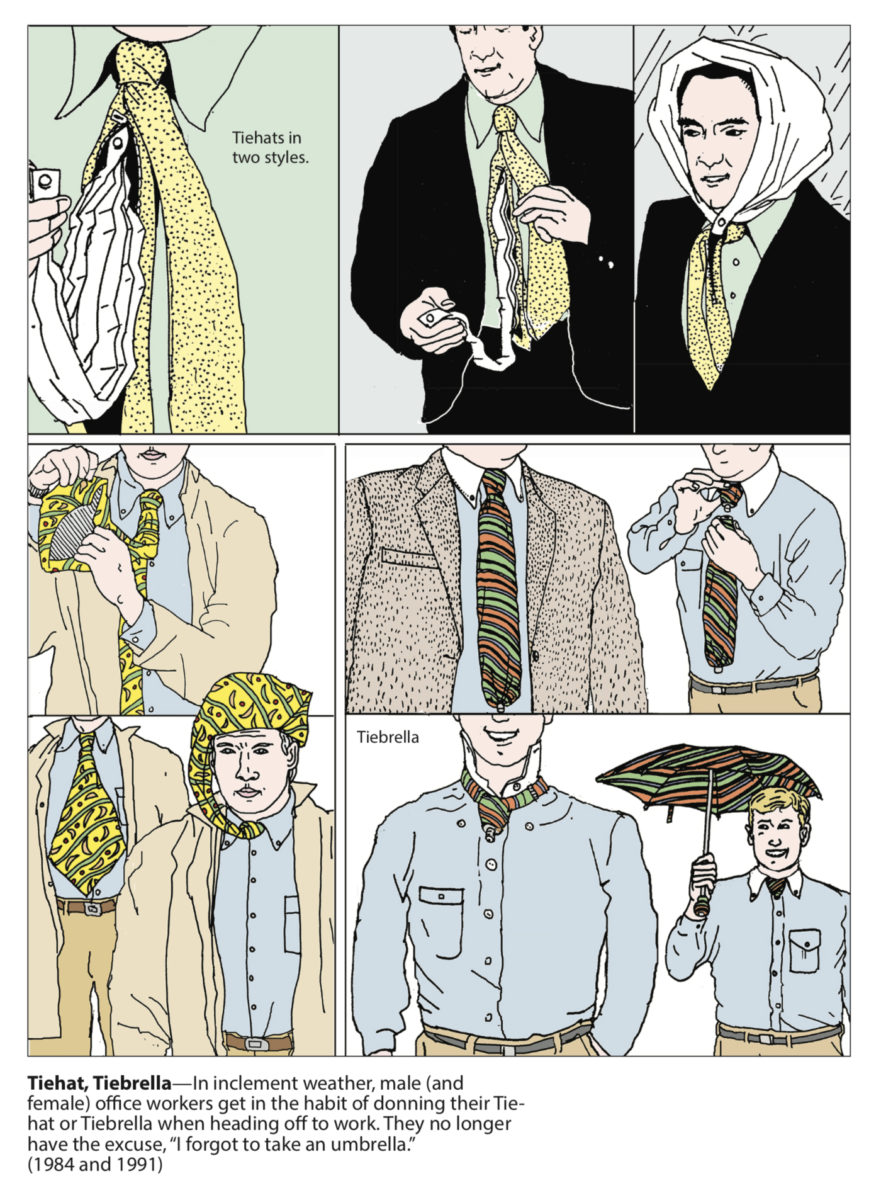

No one has admitted that my work inspired their particular product. Yet my work was in circulation through my books for many years. An artist at THE SIMPSONS show told me my 1991 book, PUBLIC THERAPY BUSES, was passed around in the office when it came out. Earlier, I found a group of product designers who say they passed around a copy of my 1984 book WHAT THE WORLD NEEDS NOW. Products suspiciously similar to ones featured in my books have been produced! They include Google Glass, Roomba vacuum cleaner, backpacks with body armor for school children, helmet cameras, skateboards for policemen, books printed in shops as you wait, whole mouth toothbrush, automobile periscope for seeing past traffic jams, office computer stations combined with exercise machines, workstations with built-in beds and many others. In general, I could sense that combination products, where practical, would become more common.

Having produced art for publication since the late 1960s, what do you think about today’s trends in art, illustration and product design?

I began creating artwork for publication in 1966. At that time, Illustrators relied on “art scrap” or magazine clippings for reference material. The World Wide Web did not become available until 1994. Gradually, there has come an explosion of worldwide sharing of ideas as well as access to ever more design tools, and to universities and design schools offering use of the latest equipment. The quality and quantity of artwork produced internationally has grown exponentially. Currently, I have become a fan of the work of new illustrators like Katie Fouquet, Pia-Melissa Larouche, Jakob Hinrichs, as well as cartoonists—especially female—like Marc Bell, Adrian Tomine, Julia Wertz, Gabrielle Bell, and Sarah Glidden. There are now college courses in how to create comics!

Can you tell us more about this position as a futurist at Honda? Sounds like a kid’s dream job.

It was not a dream job in the way one might imagine. I am often asked, given how I like to design unique and sometimes strange products—especially automobiles—if I helped design vehicles at Honda. No, not at all! I was interviewed by the compact, eccentric, Japanese-born boss in charge of a small, four-member future trends-tracking group. I waited until the end of the interview to shove a signed copy of my comics-format, future-themed book, PUBLIC THERAPY BUSES, across a huge shiny wood conference table. He sank into his chair, began reading the book, and stopped interviewing me. The personnel officer reminded him that he was supposed to interview me!

He loved comics, was an artist himself who graduated from Art Center in Southern California. He wanted to hire me immediately. The year was 1995 and I felt lucky to be hired at age 57 with no experience working in the auto industry. I was hired to research future trends, and the job required me to travel to interesting conferences in the U.S. and Canada and to report on my research in PowerPoint presentations that discussed our findings. The audience was usually jet-lagged or sleeping upper management Honda engineers from Tokyo. Certainly in many ways it was a dream job.

What do you think about the border your work inhabits between joke, dreams and actual industrial design?

Via their imaginations, designers invade a realm that is at a rarified idea level, where they think up ideas before they apply them at the product design level. Because I knew I lacked the training of an actual product designer, I tried on purpose to make many of my images impractical, BikeVest et al. At first most were foolish, humorous and unserious and unworkable yet later on, in 1991 I was creating plausible, fantastic, futuristic concepts. A 2016 article in NEW YORK MAGAZINE lauded me as a cartoonist who predicted the future.

What’s next for you?

The timing of this interview coincides with a time in my life I am winding up several art-related projects. I just recently completed two large books for publication in China that included new work, and am finishing up preparing for a gallery show that includes my artwork in Saarbrucken, Germany, titled REVOLT OF THE MACHINES, opening in early 2021.

Thanks a lot for your answers Steven!