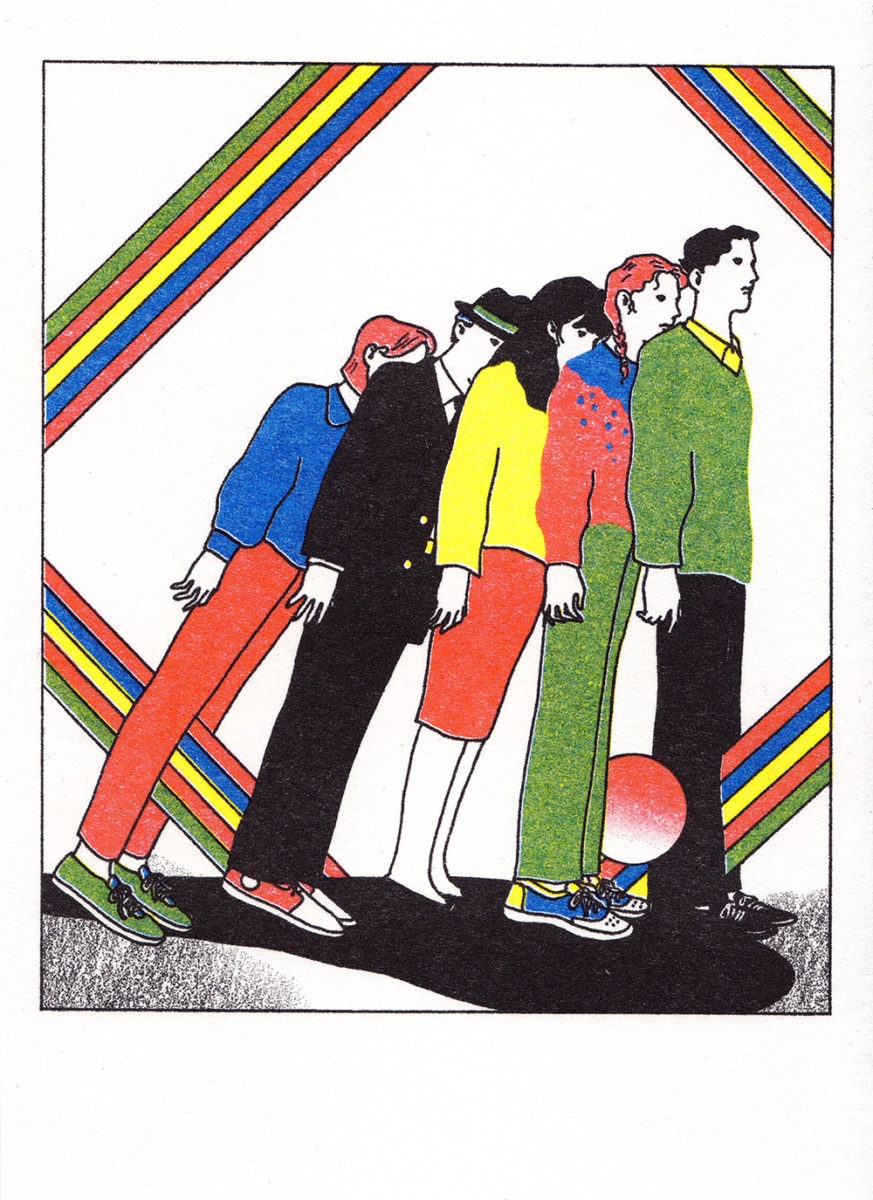

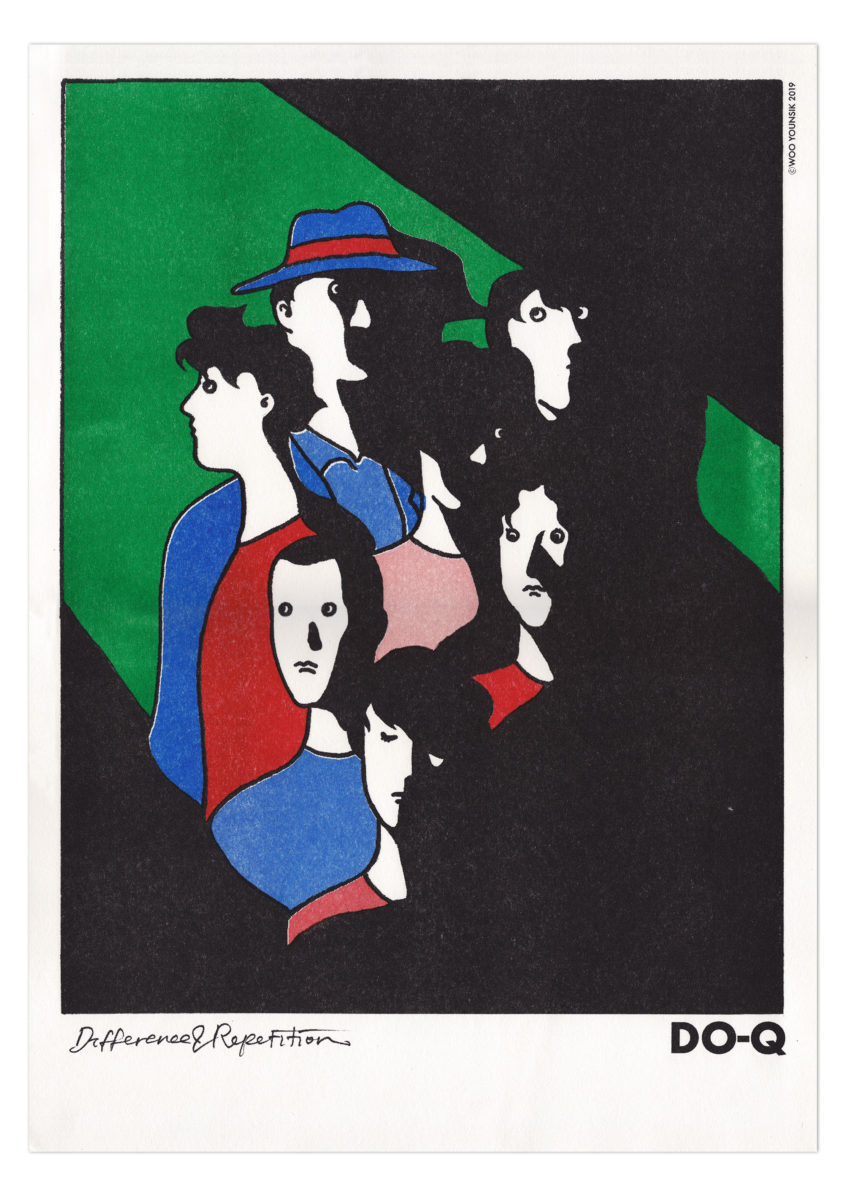

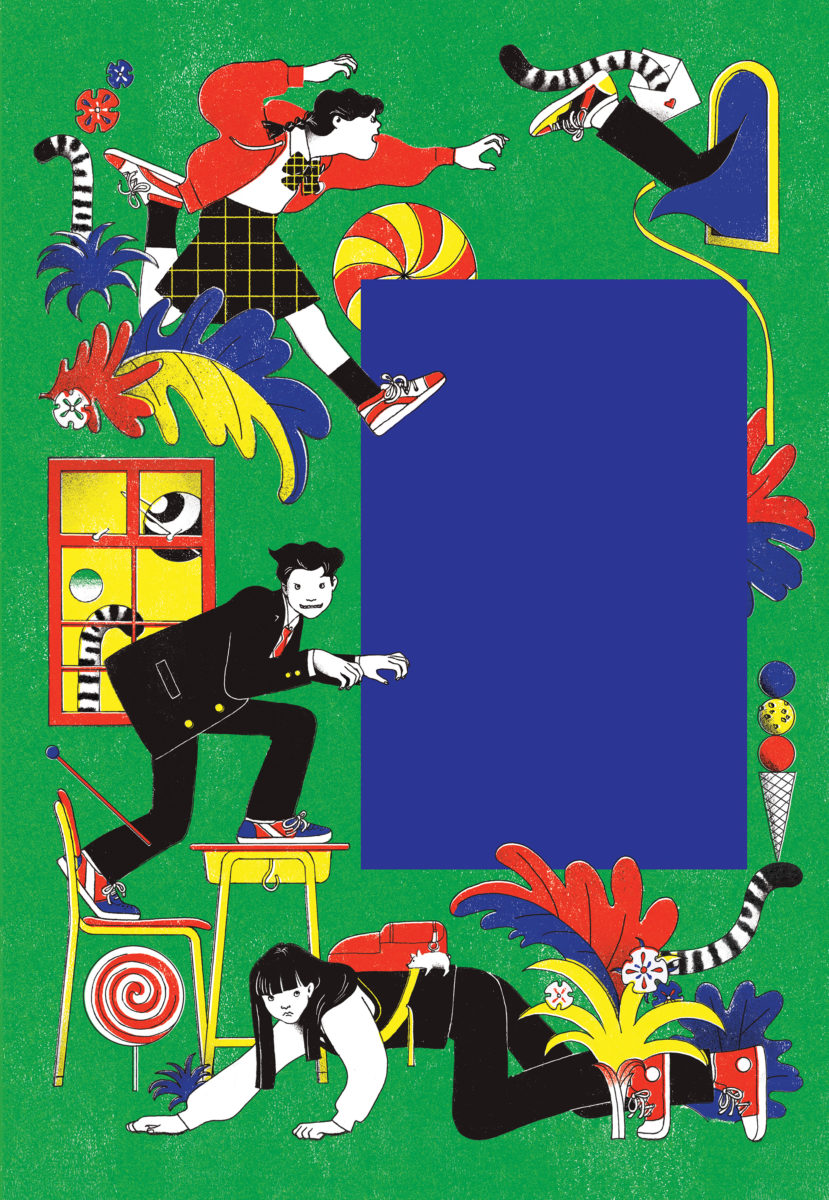

I am leaving more space for my unexplainable, obsessive habits such as using stripes and primary colors.

Younsik Woo

ART . May 6th, 2020Can you please introduce yourself?

If you find someone wandering, holding a big bag, looking for a nice cafe to work, every day, on the edge of Seoul, maybe it’s me.

What is the main part of your work?

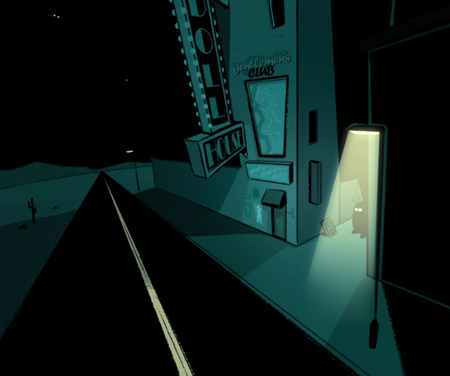

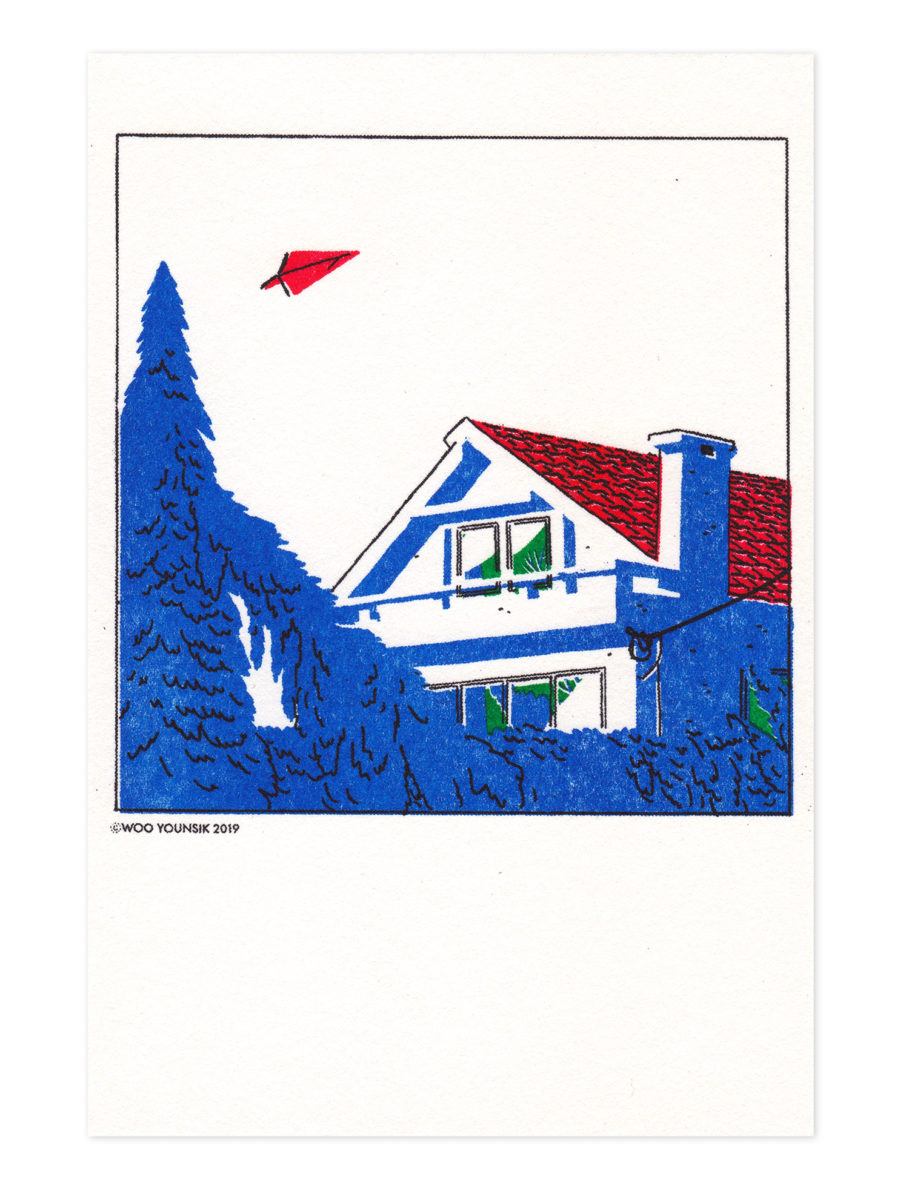

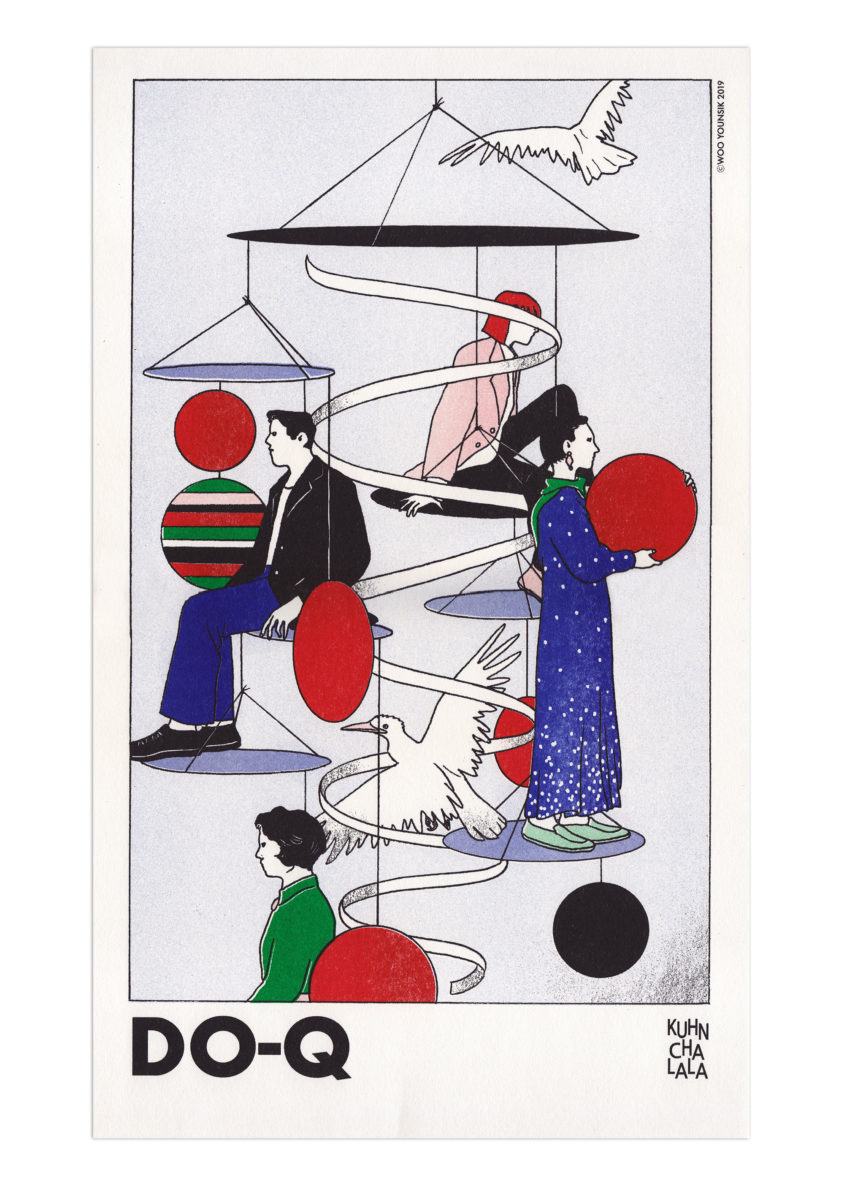

I started my career as artist by creating comics, and made my living by doing commissions from publishers. But I consider my personal illustration work as the most important part of my work, which I sometimes turn into posters. I did it just for fun at the beginning, but it became something more important for me once I started selling and promoting those works. Now I’m trying to create things whenever I can. Seems like the types of commissions are gradually becoming more and more related to my personal work as well.

What do you listen to when you draw?

It depends on what I’m doing. I rarely listen to music during the conceptual stage of my work. I don’t think I have the ability to listen and think at the same time. When sketching, I would listen to something ambient, when drawing pen lines, indie or classical music. When working on laborious stages like coloring, I would deliberately pick some rock or electronic music, or latest hits.

I think your work has something very nostalgic, can you tell us about that?

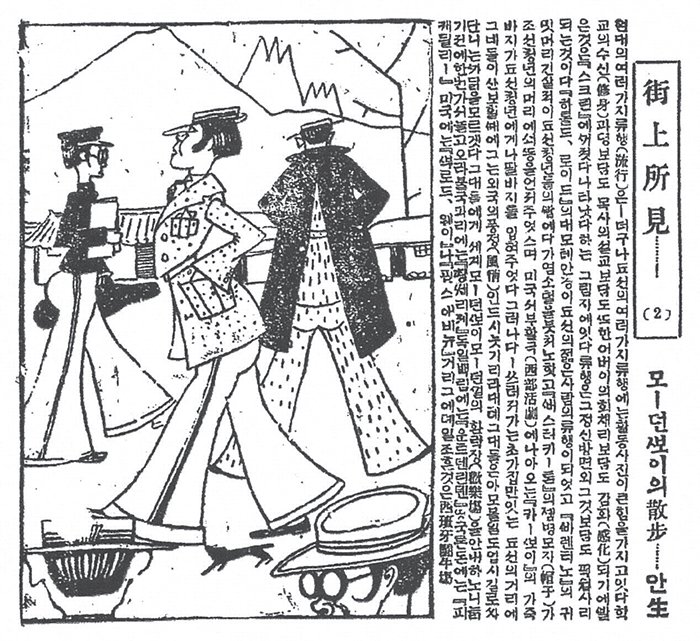

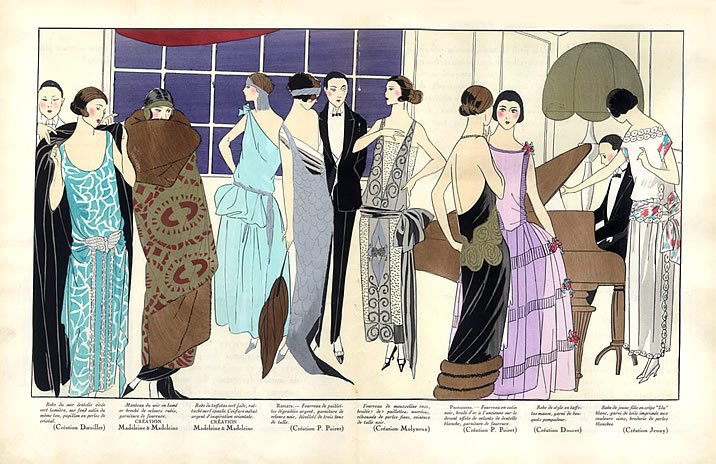

I think it comes from when I was deeply into by antique prints like satirical cartoons and fashion illustrations of the 20s-30s.

I was intrigued by the use of bold pen lines, by unique exaggeration and by the use of primary colors. I wanted to learn about print making techniques, so I ended up frequently visiting print shops to create wood block prints and etchings, which turned into the riso prints and the silkscreen prints that I create nowadays. My current work brought me to reinterpret the techniques and styles of antique prints.

What inspires your style? How did it evolve through the years?

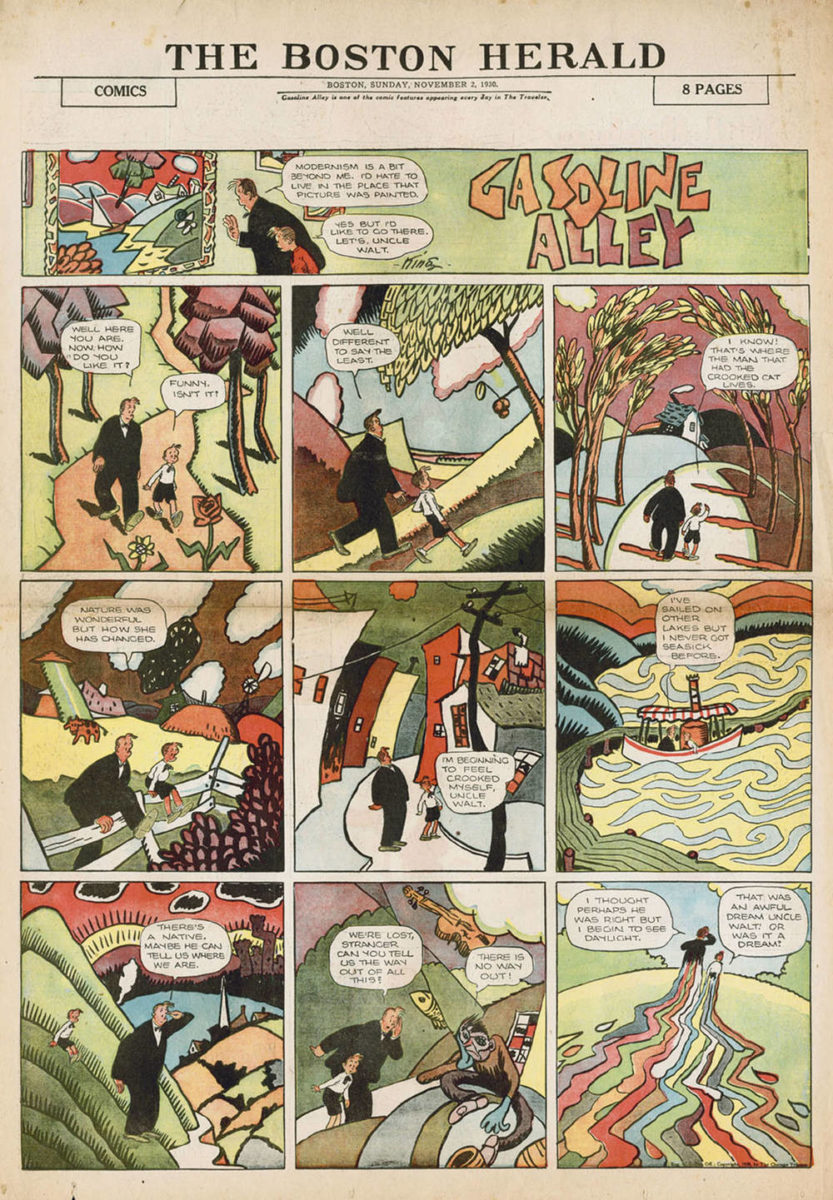

Up to my 20s, I absorbed everything that came my way. I was greatly influenced by analogue prints as mentioned, and also by Japanese manga, Korean underground comics, the ‘60s British culture, Art Deco, Bauhaus, etc. After a period of acceptance, I met some kind of inflection point. I felt like it was time to make some picks from all the past influences and letting go of everything else, so I could pay more attention to my own sense of form. I am leaving more space for my unexplainable, obsessive habits such as using stripes and primary colors.

What was your favorite comic as a teenager? And now?

When I was a teenager, Korea was submerged in an (illegal) influx of Japanese culture. I also was a passionate manga lover. I was a big fan of Atsushi Kamijo, Akimi Yoshida, Maki Kusumoto, Riichi Ueshiba, and numerous other well-made animations. I liked pieces with unique styles that are masterfully finished. Now I’m no longer able to have fan spirit like that time, and I’m a bit sad about this, even though it’s an inevitable change. Currently I like pieces that make me think I want to try out something similar, like Manuele Fior’s L’entrevue. Also I am most found of and supportive of the works of my fellow artists.

How did you get access to this Japanese culture?

It wasn’t as difficult as you think. In the 90’s most of Japanese content was publicly prohibited, but there were thousands of pirated editions, many shops selling copied video tape, some private screenings or meetups.

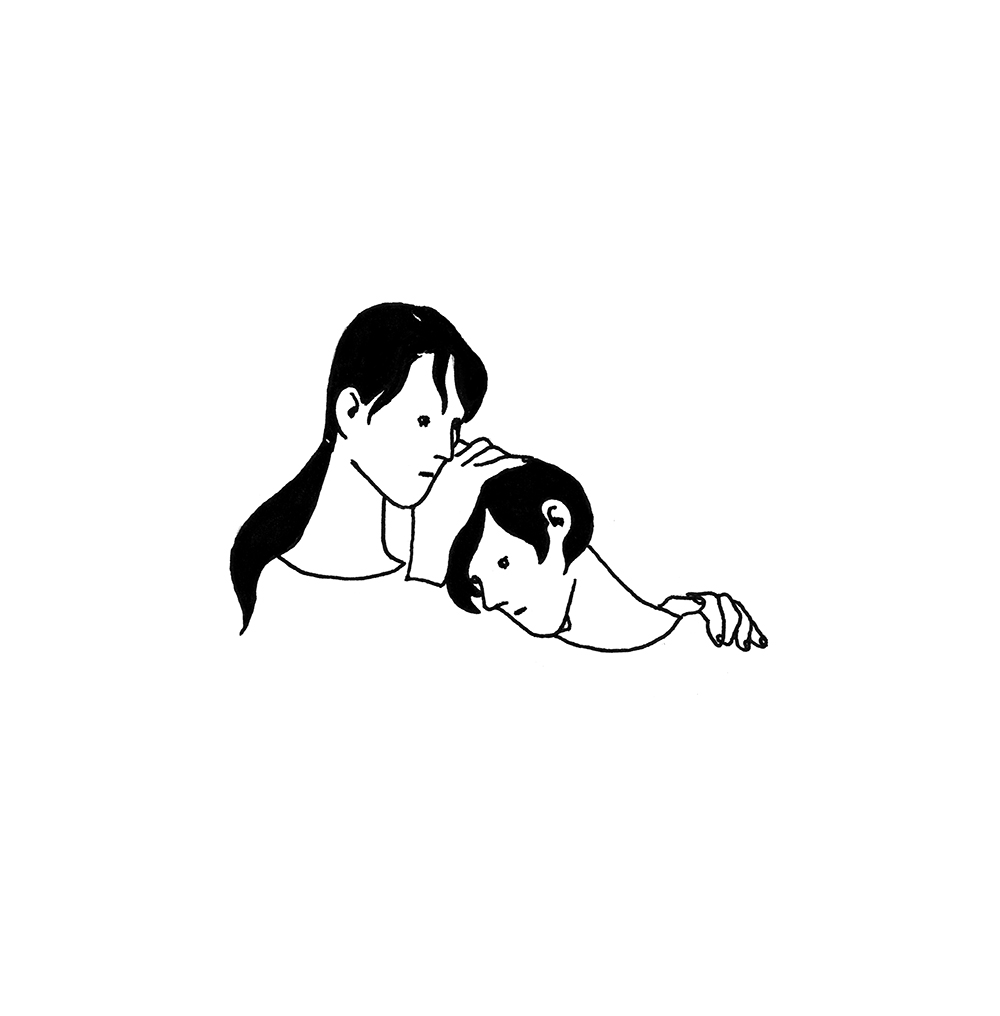

What do your illustrations talk about?

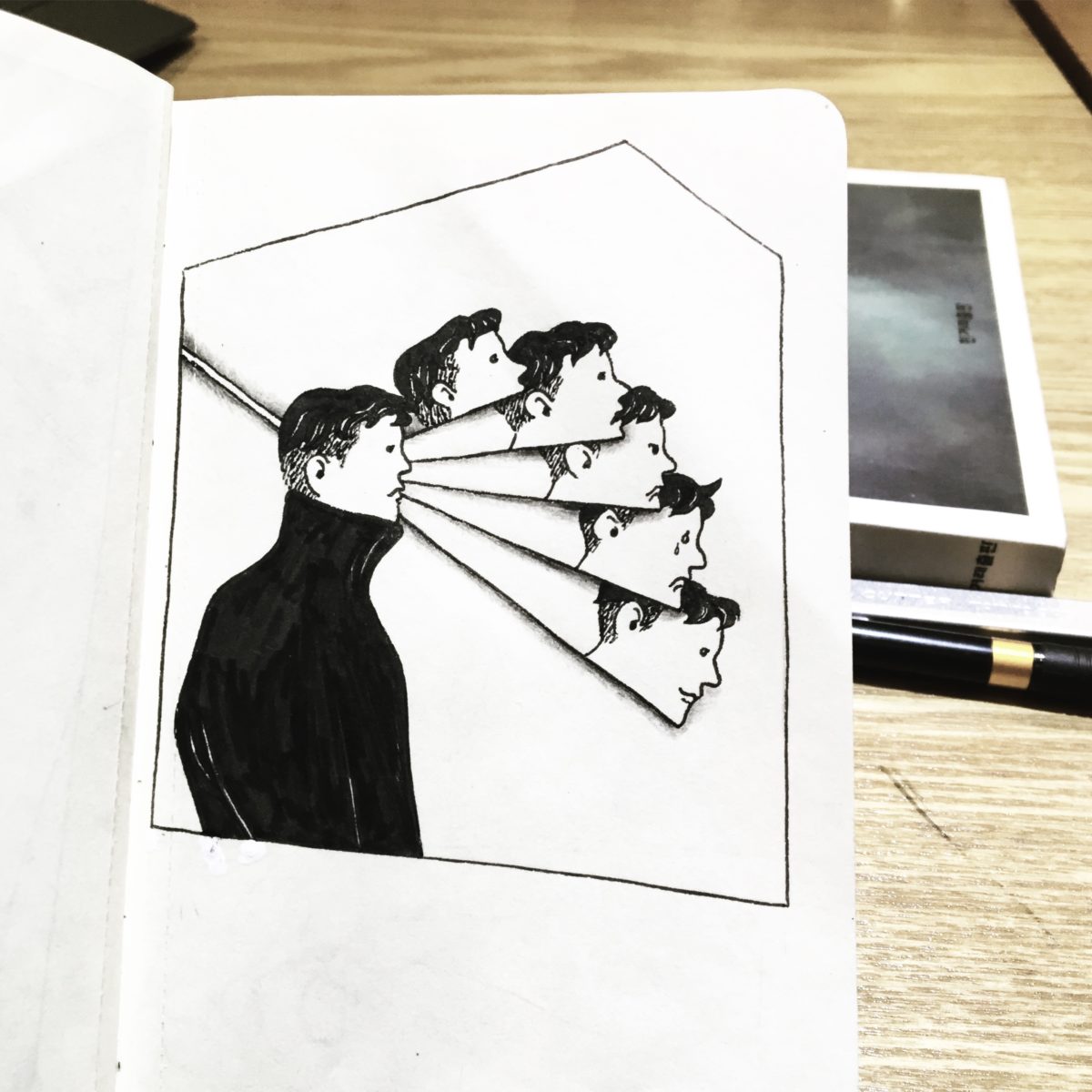

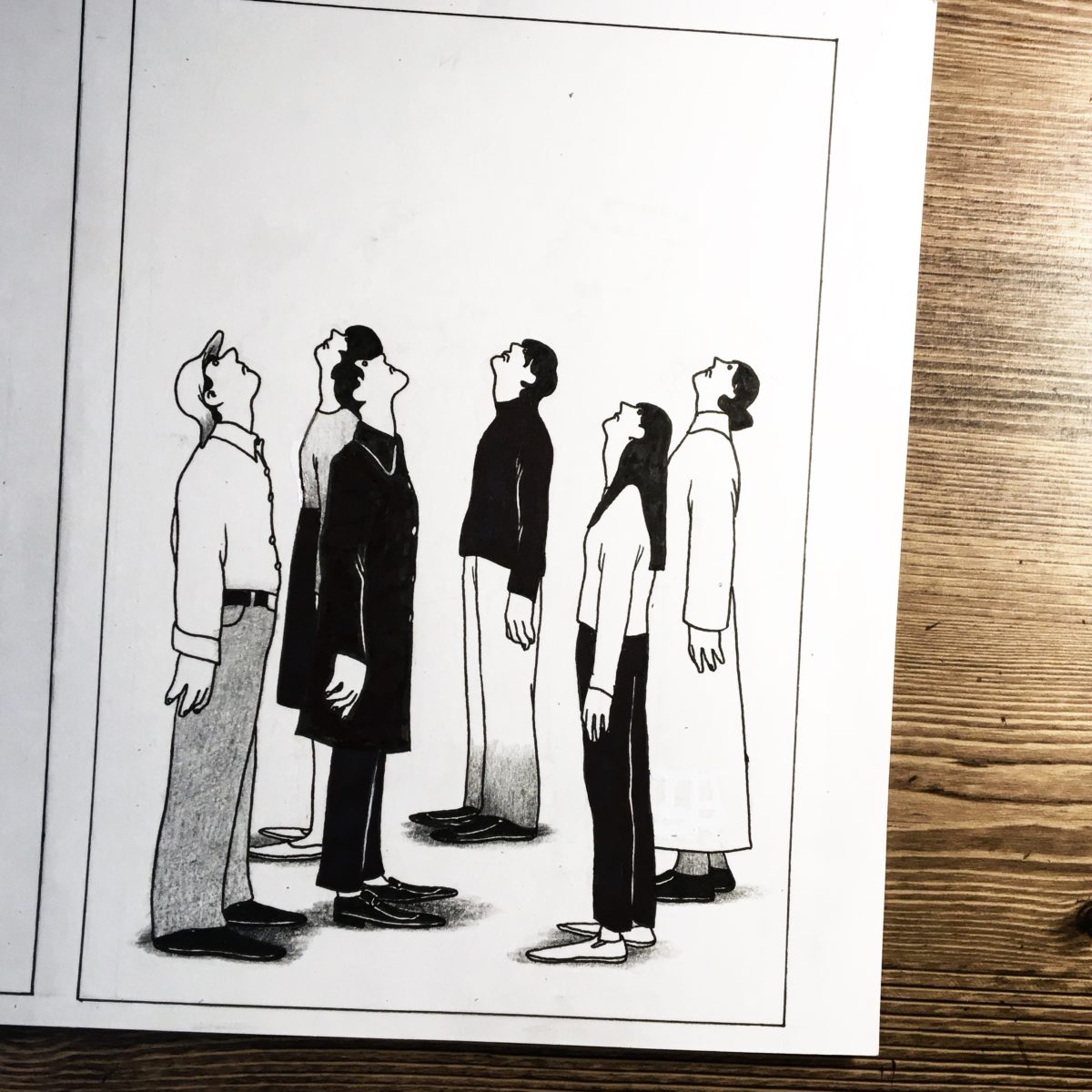

I draw crowds of people often. It is because I think a lot about human networks. I am very interested in chain reactions caused by social and personal connections within relationships. If I had not gone into the arts, I would have probably ended up studying sociology or counseling. Usually my work starts from spontaneous imaginations that emerge under these interests. But I don’t intentionally try to insert a message into every single drawing. It seems my interests naturally seep into the work when I just focus on the attractive images.

Recently I had a chance to hear some feedback from my clients. They said that the straight-faced character of my illustration is neither optimistic nor pessimistic, but neutral, and that it doesn’t clearly represent some specific attitudes. After hearing this, I noticed there are some things I unconsciously want to resolve in my drawings. The environment around me tended to be very hierarchical and required clear answers about what was right or wrong. I realized that my long-lasting resistance to this made me want to eliminate those tendencies in my art. It made me to erase hierarchical aspects from gender issues, morality, beauty, causality, and form. Even I draw landscapes, I try to equalize what is more or less important. After acknowledging this, I felt like this attitude can be a guidance in my future work.

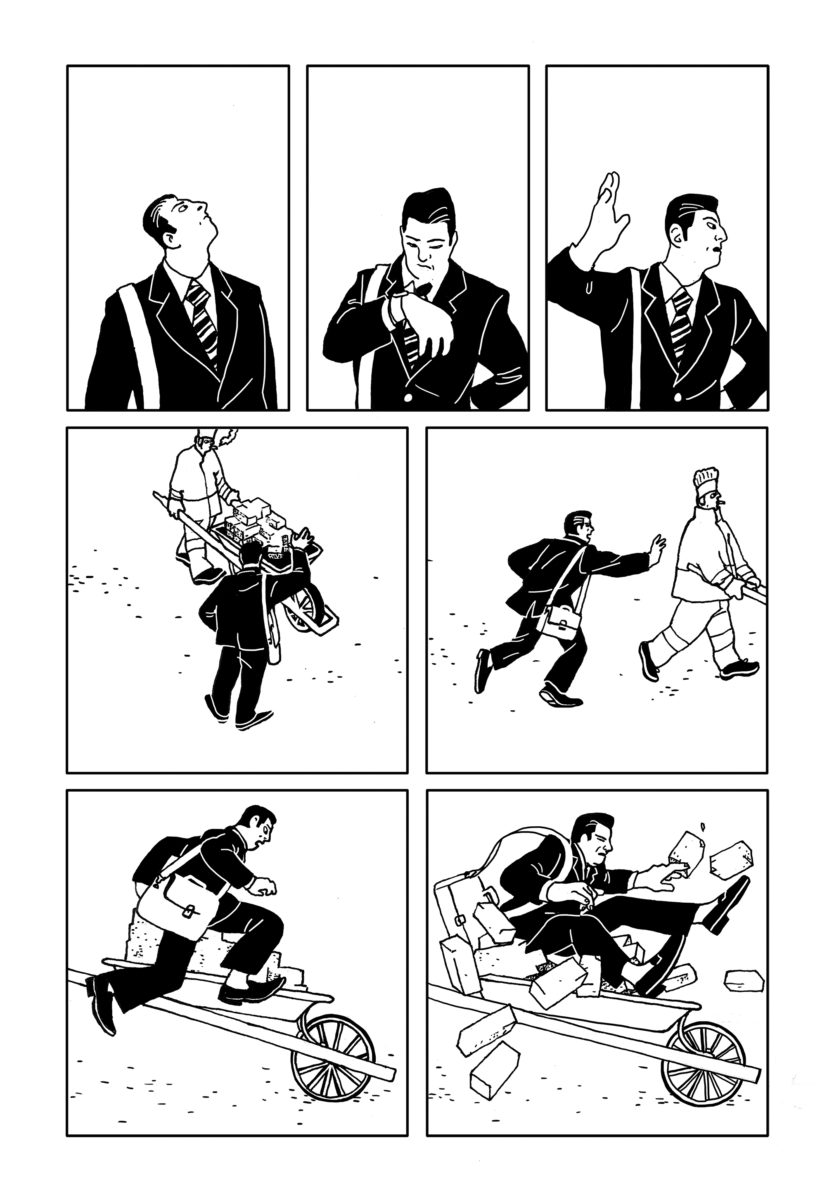

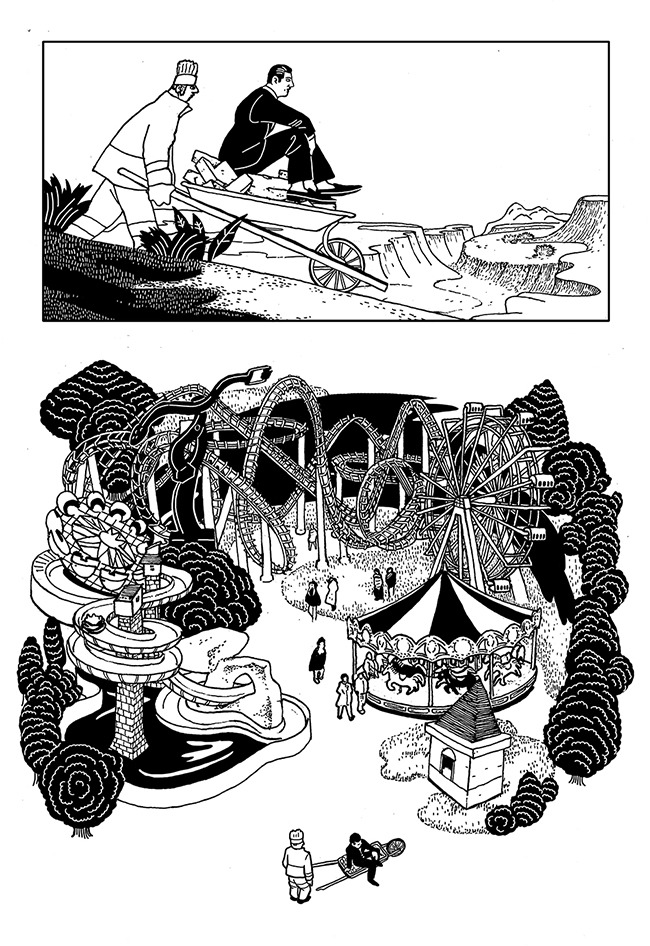

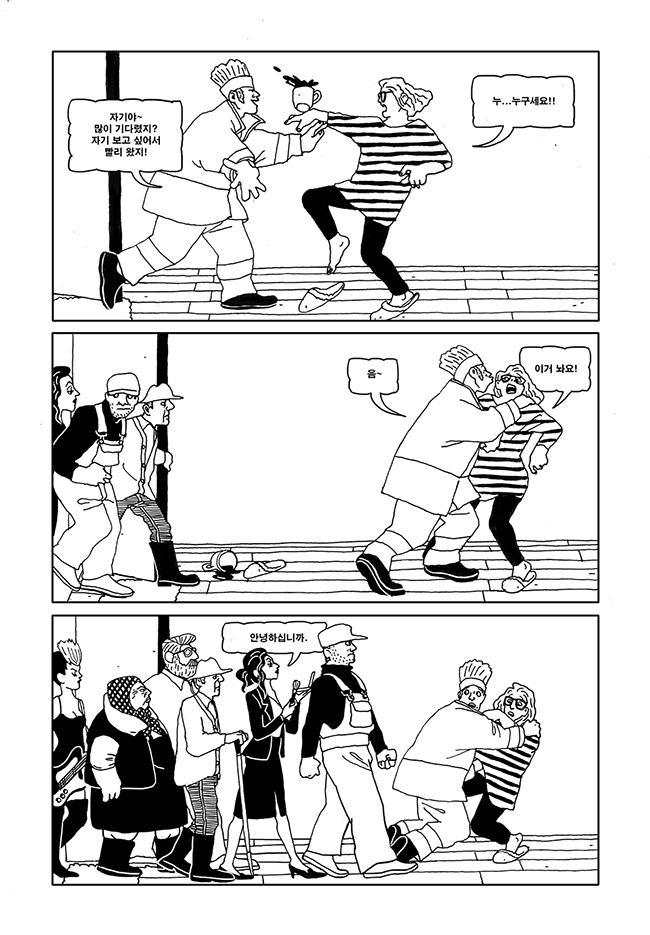

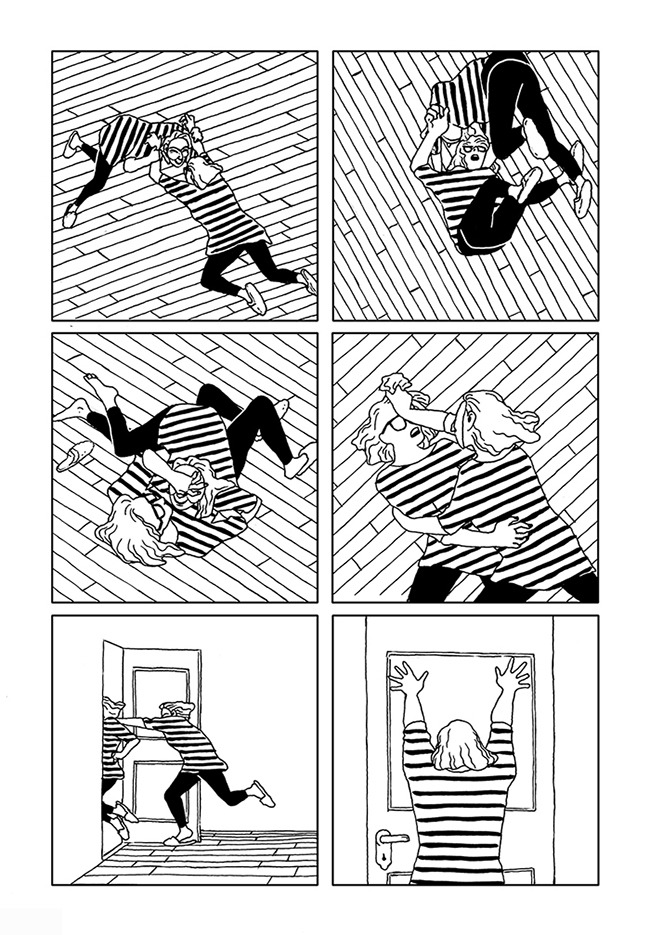

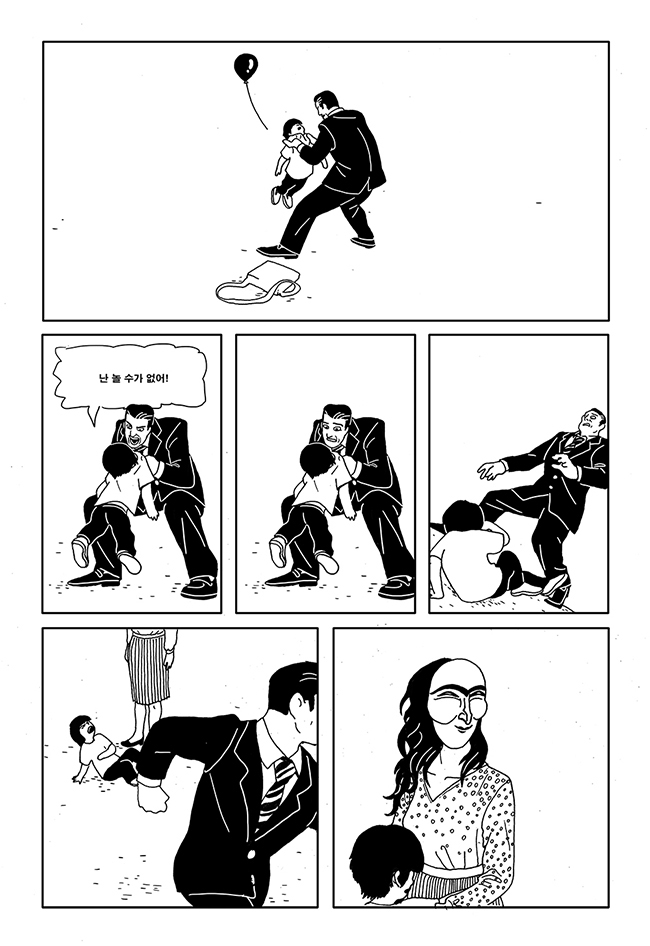

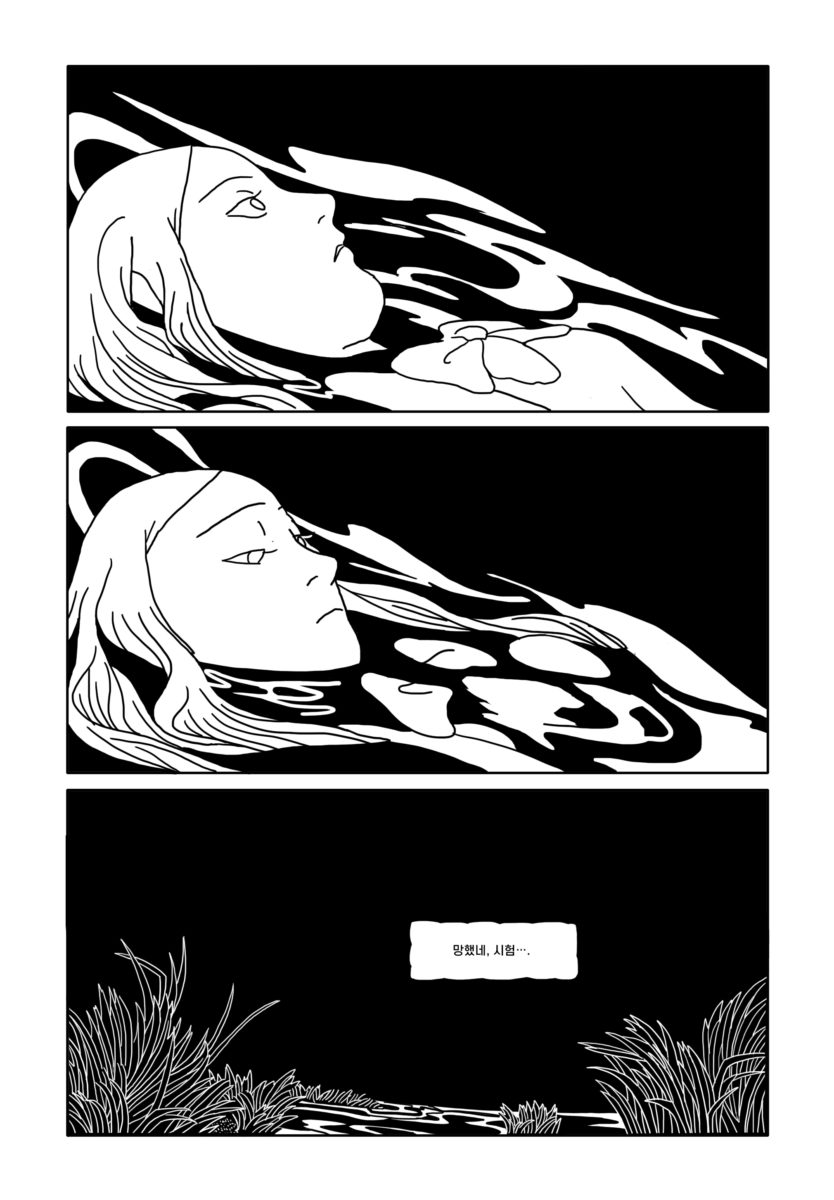

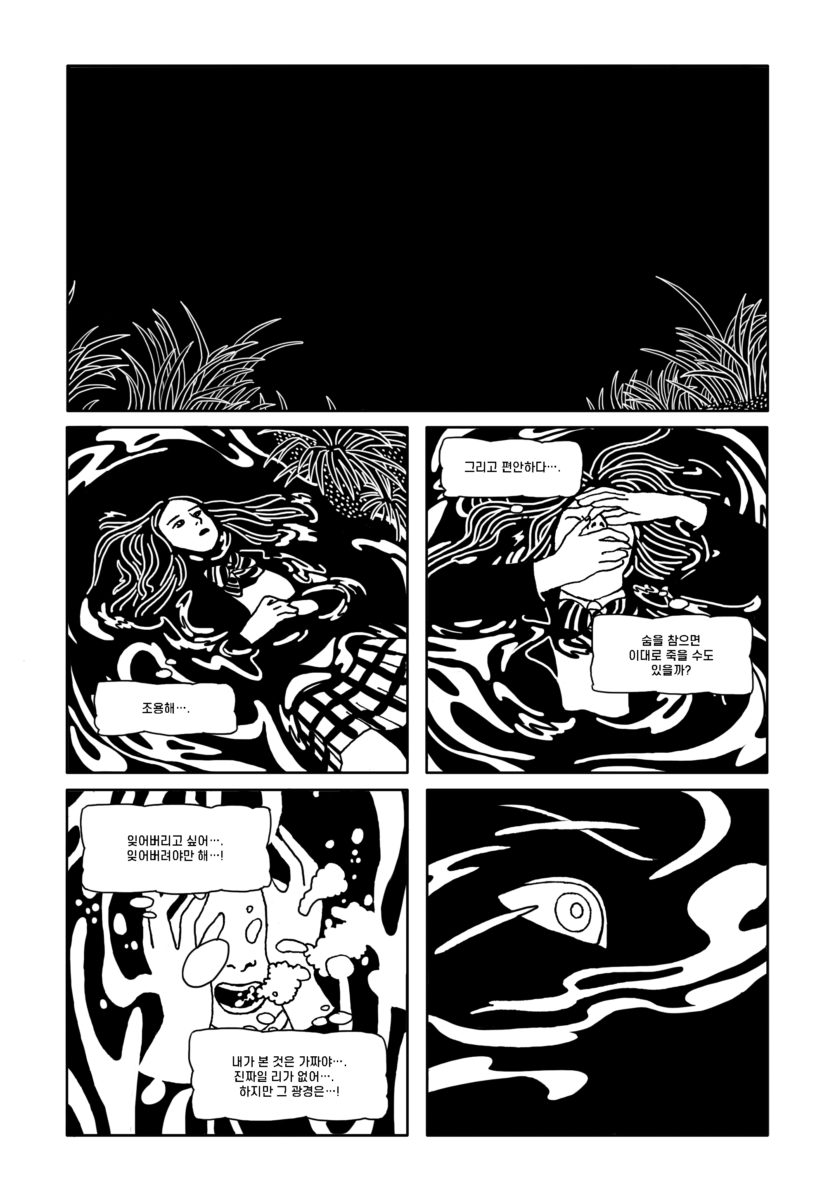

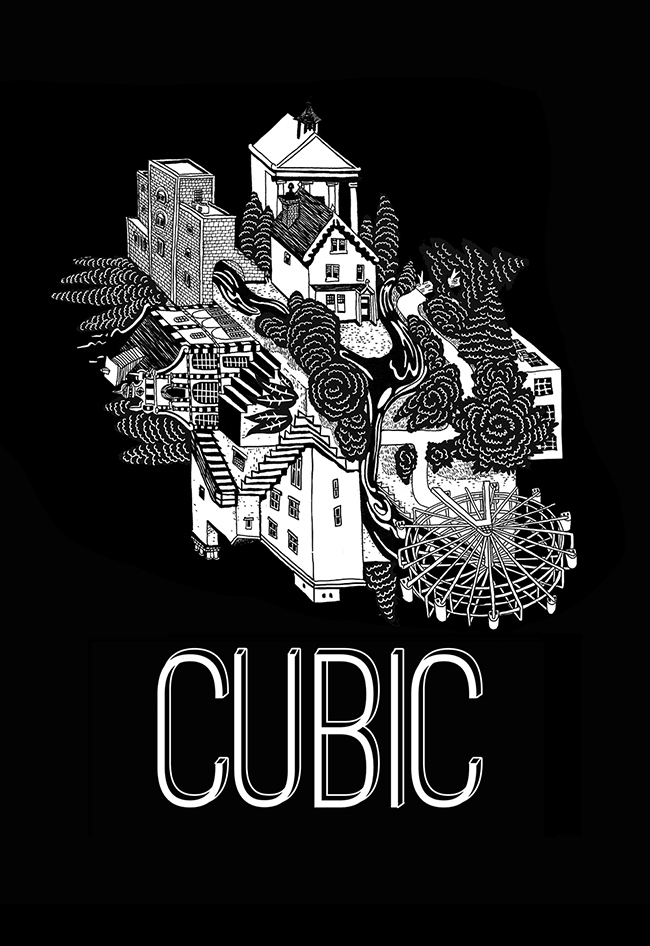

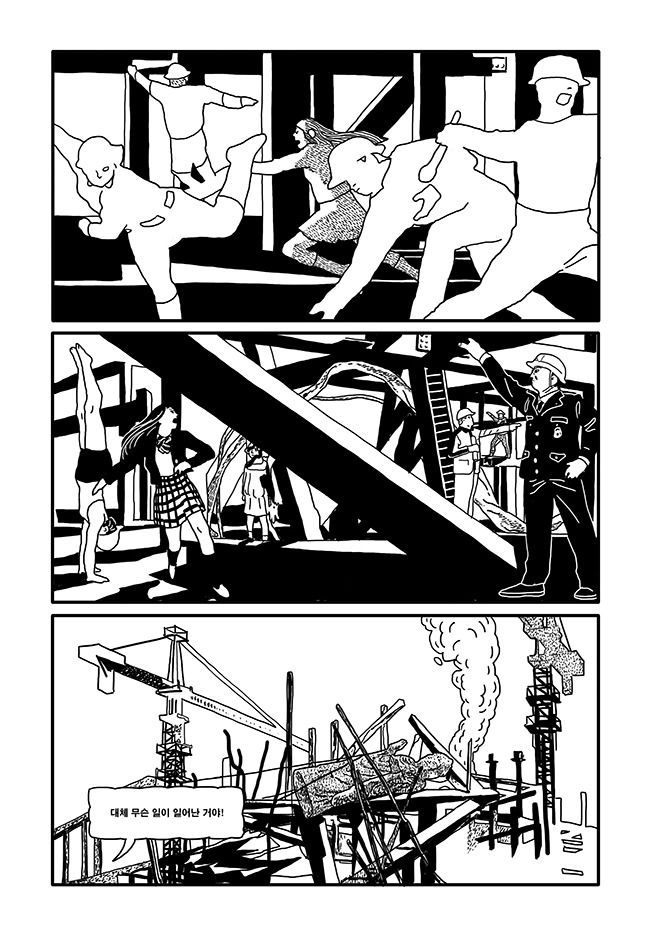

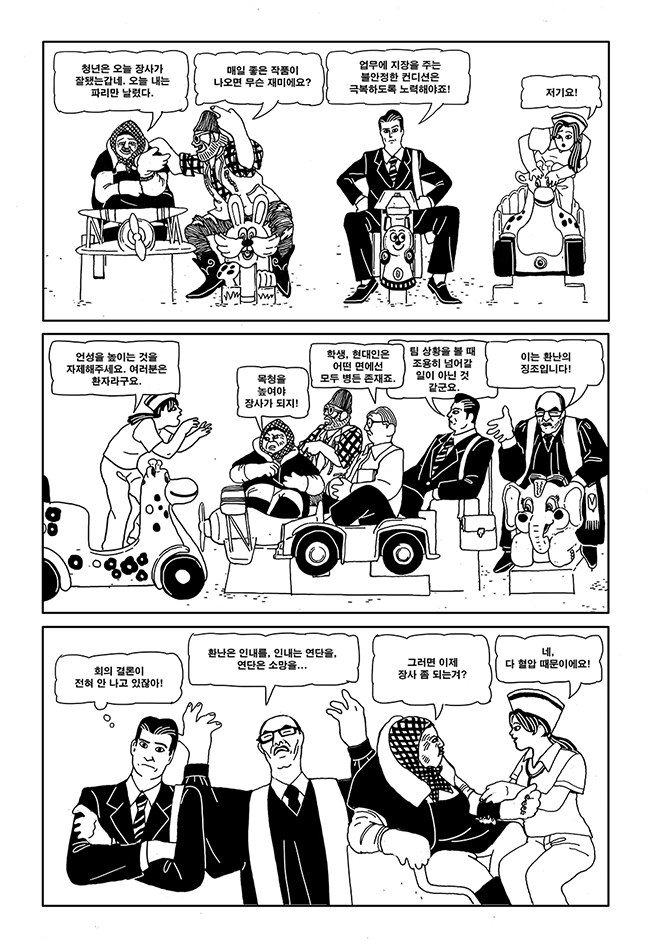

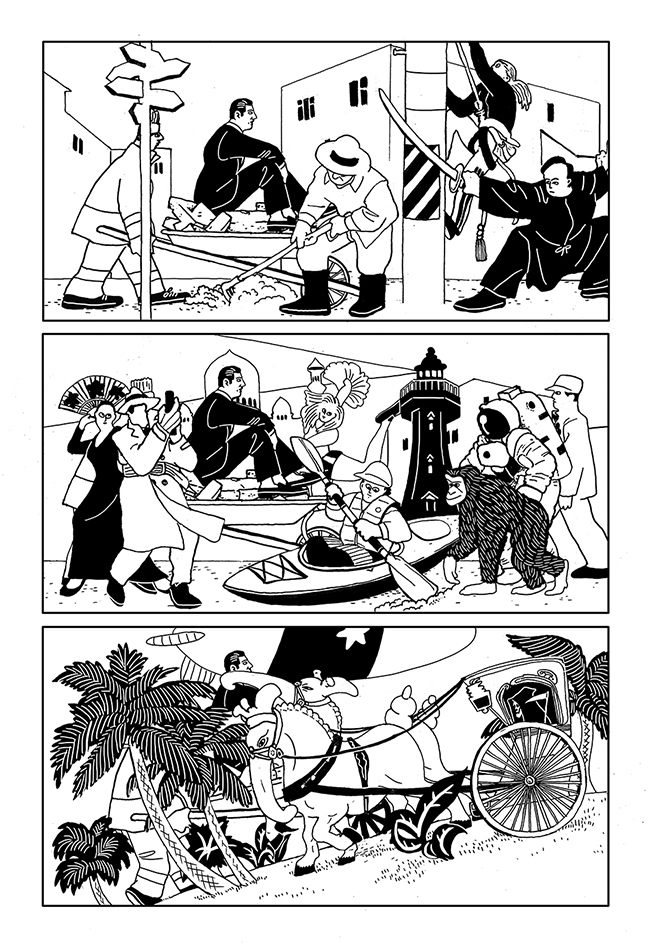

What is this comic about ?

<Cubic> is a 160-pages book. In the book, a young child’s prank turns the entire world upside down. Most of the people are unaware of the change, running into trouble when they keep on living the same way they did the day before. The story is about the family living in this world, trying to help one another find a home to return to. After releasing it in series with Quang comics from 2014 to 2015, I published this comic book in print personally.

What would be your dream project?

I have an ambition about my work’s size. I first plan is to produce silkscreen prints this year. One of my dream project is to do a public installation. I imagine how amazing it would be to get close to the public and to see their daily lives through it. I often joke about wanting to collaborate with the city of Seoul.

To finish, can you share with us some artists or artwork that you really like?

A lot of artists come to my mind, but to name a few that I currently follow…

Arielle Bobb-Willis

Changchang Yoo

Aaron Lowell Denton

Ramhan

Icinori

Younsik Woo is an illustrator based in Seoul. You can follow her on instagram and on tumblr.