Jason Koxvold

PHOTO . May 31st, 2017

Interview with the British photographer, Jason Koxvold (b. 1977, Liege) – based between Brooklyn and Upstate New York.

His latest series, ‘KNIVES’, is a truthful look at a rural community victim of the effects of globalisation they didn’t had any control over – this documentary is also deeply linked to a typological study of knives, whose industry was the basis of the region’s economy. The story of this town is the story of many more in the USA and the in the world.

ARTIST STATEMENT

KNIVES is a project made over several years, using documentary photography to trace the shifting relationships between masculinity, myth, and violence in a rural town whose economic base remains eviscerated by globalisation.

The cutlery industry formed the economic backbone of New York’s Hudson Valley for over 150 years, when the Schrade knife factory abruptly moved production to China in 2004, leaving 500 men and women out of work. The town’s maximum security prison, Eastern Correctional Facility, became the largest employer in the area, shielded from the wider community by layers of secrecy. As businesses continued to close during the decade that followed, drug abuse, mental disorders, and rare cancers have become more widespread.

KNIVES operates as two intertwined stories: one, a typological study of knives crafted in the region since the rise of the cutlery industry, provides connective tissue to the other, which deals in the realities of the local community, both within the prison and without. The project serves as a microcosm of the larger issues facing the United States, grappling with the effects of automation and outsourcing, cuts in services, and the rise of identity politics.

___________

How did you find this town of Wawarsing and why did you choose this community in particular?

I built a house in the woods here nearly a decade ago, so these people are my neighbours. Once I started to understand the history of the place, I knew it was a story that had to be told.

How long this series took you and what did you learn from it?

The series has taken two years, give or take. It gave me an inside view into the less-visible effects of neoliberal economic policy; it taught me a lot about empathy.

Can you choose 2 characters you met and tell us a bit more about them and their lives?

The character I’ve photographed the most is the curator of the knife museum. Coincidentally, he was also a prison guard at a local prison for over 25 years. He describes his life as a history of violence, and his family is either dead or estranged. When his wife left him, he begged the military to send him to Afghanistan, “so that he could kill some people”. I photographed over 300 knives at his house.

The other character I have photographed a lot is Dave, who lives quite near me. He studies the bible extensively, and paints the exterior of his house with graffiti depicting a mixture of Christian and Jewish symbology. I was initially very apprehensive about photographing inside his home – there were knives strewn around the floor when I first visited, and he is haunted by spirits who “scratch at his window all night long”, but he’s a lovely guy and we’ve grown to trust each other.

Give us a song and a movie that you think fits well with this series.

Julia Kent’s album, Asperities, fits beautifully with the series (and we use it on Elijah Kent’s documentary about the project). I just watched a film called The Other Side, by Roberto Minervini, and although it deals with very different people, some of the themes are similar.

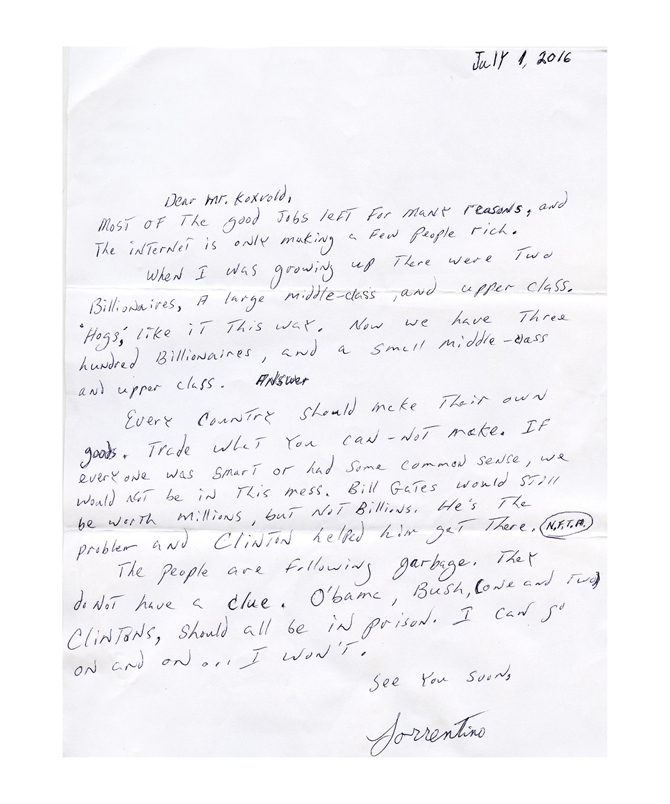

Tell us more about this letter? What’s its background?

The letter is from a prisoner I photographed inside the maximum security facility. He’s incarcerated for several decades after stabbing his wife more than 60 times in the head. He’s a big fan of the Beatles; he doesn’t like modern music very much.

What’s the real meaning hidden behind the knife representation?

For me the knives present a powerful intersection of symbology. They’re essentially tools of violence, at some level. Some of them are works of art in their own right. They represent a disappearing craft, but also a fundamental truth of neoliberal economics: if the owners of the business can make more profit by doing things a different way, they must do so. To not do so is not even a possibility. In this case, a man bought the company, laid off all the workers, moved production to China, and then sold the reformed company to Smith & Wesson for around $80 million. The only cost was the blood of the town of Wawarsing.

How do you feel now when you think about these people?

I feel empathy for their situation, which is a common one in the United States. By and large, this is a town that voted for Donald Trump, who is not known for building American industry; his business model follows the neoliberal playbook. A lot of Americans believe that the reason they’re out of work is because of Chinese people and immigrants; they believe that ‘globalists’ are the cause of their pain. And while this is somewhat accurate, the real truth is that there’s a schism, an existential crisis, in the American value system.

One of the knives is called ‘Nigger Chaser’- was it the actual product name?

That is the name that the knife was given, unfortunately. There are printed advertisements from the time that carry the name.

What camera did you use for this project and why?

I used a combination of Alpa and Mamiya cameras with a Phase One back. I recently transitioned from large format film because, much as I love it, the process had become too cumbersome and too expensive to make a large, ambitious project.

Do you have a knife? how is it?

I own several Schrades, some of which were given to me by the museum, some of which I bought for research. The original ones are beautiful, hard-working knives, and you can see the craft in them. The new ones, made abroad, will not last long and are not very interesting to look at.

What’s next for you?

After this project, I have a series I’ve been working on simultaneously called BLACK – WATER, that takes a long look at the cultural and economic effects of constant war. I’ve been photographing it on military bases in Afghanistan, Kuwait, the UAE, and inside the United States.

What are you going to do just after having answered to this final question?

I’m heading to the gallery to supervise the installation of the show for today’s opening!

Merci Jason.